Repeat Offender

by M. Faust

“I related to the material when I read the script, and I don’t know why, it’s like an obsessive behavioral pattern on my part,” says Martin Scorsese about The Departed, his first gangster film since 1991’s GoodFellas. (Appropriately it was produced and released by Warner Brothers, the studio that invented the gangster genre in the 1930s with the films of Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson.)

Lest you fear that Scorsese is repeating himself (as some accused GoodFellas of recycling his breakthrough film Mean Streets), The Departed both revisits classic Scorsese territory while breaking new ground for the man many consider to be America’s greatest living filmmaker.

Adapted from the Hong Kong hit Infernal Affairs (and its two sequels), The Departed is based on a premise that sounds like a criminal version of an opera buffa story. Boston gang lord Frank Costello (Jack Nicholson) places Colin Sullivan (Matt Damon), the son of a dead partner, into the police academy so that he can have a mole on the police force. In Colin’s class is another kid from the same rough South Boston neighborhood, Billy Costigan (Leonardo Di Caprio), who is sent undercover to infiltrate Costello’s gang. Both organizations are patient enough to spend years letting their man become a part of his surroundings, years in which the lines between cop and criminal fade for both. And when the cops and the crooks both figure out that the other side has a spy in their ranks, guess who they assign to find them?

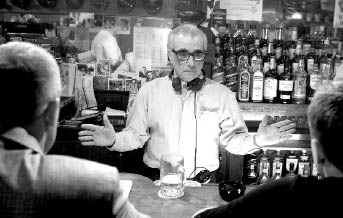

Speaking with a small group of reporters at a Manhattan hotel last month, the affable 64-year-old Scorsese retains his characteristic precise rat-a-tat diction that sometimes makes you feel like you’re interviewing a stock market ticker of the kind that hasn’t been seen since the heyday of the classic Hollywood films he loves to reference.

Asked about the differences between these Irish hoods in Boston and the Mafioso from his own upbringing in Manhattan’s Little Italy, he takes the opportunity to correct the notion that every New Yorker whose name ended in a vowel was “connected.” “It isn’t that I met Mafioso,” he explains, “but that I grew up in a working-class environment, and part of that environment was organized crime. It’s a difficult thing to talk about because the people who were trying to live a daily life, trying to provide for their families, always get offended by this sort of thing, I always hear complaints from old friends about the kind of pictures that I make.

“In [John Huston’s classic crime drama] The Asphalt Jungle, there’s a line that crime is simply a left-handed form of human endeavor. When you go that way in your mind, and live that way on the street, it doesn’t matter whether it’s Boston, Chicago, New York, Miami, Rio, anywhere, it filters down to survival on the street. In this film you’re talking about a society within a society within a society that’s at war with itself. There’s a war in the streets going on, and these guys know from the beginning if they make one mistake they’re killed, they’re dead. There’s no place to run or hide, none. You take that as a setting, a situation, then your philosophy becomes survival. The differences between different ethnic groups as far as ‘gangsters,’ that’s purely technical.”

Noting that he was drawn to the incestuous nature of The Departed’s story of trust and betrayal, and the context of the Irish-American Catholic world of Boston, Scorsese says that he was initially “a little nervous” about approaching a story that has as much to do with cops as with criminals.

“It’s the old cliché, it takes a thief to catch a thief, you have to know how the underworld thinks in order to play against it. It was really [screenwriter William Monahan’s] depiction of that world that made it clear to me, in terms of me working again within a genre that dealt with gangsters. I felt comfortable in the street scenes, the guys in bars and that sort of thing. With the police scenes I was at first uncomfortable, but that was all laid out in Bill’s script.” He credits some lightening of the tension to co-stars Mark Wahlberg and Alec Baldwin, who bring some over-the-top humor to their performances as a hard-nosed cop and Special Investigations supervisor. “They worked together beautifully, so that it became like an Abbott and Costello routine between them. I didn’t have to say anything to them, they just did it.”

Scorsese long ago tested the limits and uses of screen violence in films like Taxi Driver, and has not shied away from it since, as scenes in The Departed make clear. He draws a line between his own work and “films that are more like video games, that make violence look like a game. I felt that if you’re going to experience violence you should experience it powerfully and real.”

Still, he dislikes being put in the position of defending screen violence. “I don’t know if I approach it differently,” he says. “I approach it the way I experienced it, or what I thought I experienced it anyway. Some [young] people are more impressionable than others, some people just block it out of their minds; me, I was very affected by it—more by the emotional violence around me, and it’s part of what I am and who I am, and somehow it channels itself into the films. I see it sometimes as almost absurd, but that’s just the absurdity of being alive.”

Much pre-release buzz about the film has centered on a scene of drug-induced sexual excess and violence involving Jack Nicholson’s character that didn’t survive into the final print. Recalling how he had similar discussions and debates during the editing of Raging Bull and Taxi Driver over “how far you can go in a film and how far you can’t,” he feels that the the scene is presented in a way that will have the best effect on audiences.

“What you see ultimately in the film is the process of a lot of hard work, editing, previews—I previewed the film three times. Ultimately I decided that what is implicit was better than what was explicit as to what goes on in that bedroom. The hallucinatory effect of the scene is what I wanted, therefore the opera [music], the slow motion of Jack’s face—I had Anton Walbrook in The Red Shoes in mind.

“We decided to go more explicit in [a later scene where Costello meets Billy in a porno theater]. Costello’s come from three or four nights of doing whatever he was doing, and he’s out of his mind. Billy and Colin, their whole lives are dependent on him, and the man’s losing his mind. He doesn’t care if he’s caught, he’s got all the power in the world, all the drugs in the world, all the women in the world, all the money in the world, he doesn’t need it. We had a choice when we were shooting that scene, Jack and I were talking about [a prop he wanted to use—you’ll have to see the film yourself to learn what], I said it’s up to you, let me see what you want to do with it in the porno theater.”

Although Scorsese has previously resisted doing remakes (he reportedly agreed to direct Cape Fear (1991), one of his weakest films, largely as a favor to star Robert DeNiro), he claims to have had no compunctions about remaking the universally lauded Infernal Affairs. He’s been a fan of Hong Kong cinema since seeing John Woo’s The Killer in the late 1980s (he famously called it “Hysterical, and also very beautiful.”)

“I admired it so much,” he says, “but there’s no way I can emulate that. That’s a separate style—there are elements of American cinema in there, but it’s absorbed into another culture, and that’s wonderful, you can’t go near that. I felt okay because I knew that what they do I cannot do. I thought I could find my own way in this. The film I want to make next is another remake of an Asian film. I‘m only remaking Asian films now, that’s it!”

More seriously, Scorsese also found The Departed to have a particularly American resonance in the post-9/11 era. “As we were making it I realized that we were in a world where morality no longer exists. Costello knows that, he’s above that, he knows that god doesn’t exist anymore in that world they’re in. I felt a kind of despair in the story in the way that people relate to each other, particularly the ending. For me there’s been sadness and a sense of despair since September 11, and that’s what kept me going, in depicting this world, as a sort of moral Ground Zero.”

While the soundtrack of The Departed, like most of Scorsese’s films, uses songs from the period of the film, it also features something unusual for him, a score (composed by Howard Shore) that is largely played on solo guitar. When I asked him about this, he replied with comment that will come as no surprise to fans of GoodFellas: “I love guitars. I think of a wonderful film scored with guitars made by Irving Lerner in the late ’50s called Murder by Contract, and of course the famous zither score in The Third Man, which this film references for its themes of betrayal.

“All the characters here are entwined in a web, if they try to get away from each other they find they’re tied together. So Howard and I came up with this idea of a very dangerous and lethal tango, which ultimately does everyone in. We worked it out with acoustic guitars, electric guitars, different strings, dobro, steel guitar, all sorts of things like that. When the sound kicked into electric it was very strong, which could give a scene a slight edge it needs.”

Scorsese has come a long way since the NYU student and Roger Corman employee of the 1960s. But much as he may have earned his place in the pantheon of American filmmakers, he’s anything but complacent. “I’m trying to find a way to still be interested, to be on a set and work with great people like this, and it’s not easy,” he admits. “By that I mean to keep the energy going, keep the interest going and the curiosity going to continue to make films. But they have to mean something to me, and that’s always been a struggle because of the nature of the way the system is now. I’m still trying to find my way.”

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n40: The Long Journey (10/05/06) > Repeat Offender This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue