Theaterweek

by Anthony Chase

EMBODY

In her play, Embody, playwright Lauren Gunderson imagines a period in the life of Leonard da Vinci when he was, as a young man of 24, almost executed for sodomy. Using historical texts and her own imagination, Gunderson fantasizes 15th-century Florence and the web of intrigue surrounding this episode, populating the tale with fascinating characters.

Robert Tucker, a marvelously charismatic actor, plays Leonardo with mercurial energy and youthful charm. He portrays the man as absorbed in his thoughts and the wonders of the material world, but alarmingly disconnected from his serious circumstances.

The hero of Leonardo’s story enters in the person of Caterina, played by Kara Gabrielle McKenney, a lusty courtesan who is “kept” by powerful Bocha della Verità. Caterina fancies the young artist and schemes to save him by proving his heterosexuality—at least in the eyes of the authorities.

Gunderson creates very compelling characters in Leonardo and Caterina. This non-love story, which, in a charming flourish at the play’s conclusion, serves to explain the famed Mona Lisa smile, is quite engaging.

McKenney’s portrayal of Caterina seems a bit modern at first, and evokes early Hollywood sirens rather than Renaissance eroticism. She quickly finds her pace, however, and imbues the character with great humanity and passion. We ultimately find her Caterina to be a woman quick-witted enough and worldly-wise enough to be an appropriate complement for Leonardo—if only mentally. His interest in her palpable sexuality is powerful, but ultimately scientific.

The exploration of this relationship fuels the play and McKenney and Tucker strike a playful chemistry. Caterina determines that while she is saving Leonardo, she is ultimately saving herself. It’s a Renaissance Doll’s House in that regard.

Under the direction of Matthew La Chiusa, the cast handles the material most capably. Michael Votta, Chris Standart and John F. Kennedy give good performances in the contour roles. The logic of the play unfolds clearly and interestingly, and Gunderson is a confident and talented playwright.

OBSERVE THE SONS OF

ULSTER MARCHING

TOWARDS THE SOMME

Impressively affecting acting is the centerpiece of the Irish Classical Theatre production of Frank McGuinness’ Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme.

The play follows eight men who volunteer to serve in the 36th (Ulster) Division at the beginning of World War I. Dramatic irony is fueled by our awareness that the men are headed toward certain death in the battle of the Somme, which took the lives of 60,000 soldiers of the British Empire in a single day, July 1, 1916. The date was the actual anniversary of the battle of the Boyne in 1690, at which Protestant King William and Catholic King James faced each other at the River Boyne, a confrontation that ended with a decisive victory for William and the preservation of the Protestant settlement in Ireland.

The Somme, like the Boyne, has come to symbolize loyalty to the Protestant counties of Ulster.

McGuinness uses the painful pointlessness and brutality of World War I as counterpoint to the fears and desires of the young men marching into battle, and builds irony on the crippling self-absorption and provincialism that blinds them to larger truths. The specter of mortality forces certain realizations and blurs previously immutable certainties.

The playwright presents his characters in pairs whose personal needs, insecurities and values meld or play off of each other. Brendan Powers, Michael Providence, Jeffrey Coyle, Tim Eimiller, Guy Balotine, Steven Dawson, Christian Brandjes and Joe Wiens navigate the script with great commitment and power. Jim Mohr plays elderly Kenneth Pyper, the lone survivor, setting the story in motion as a flashback.

Given the excellence of the ensemble, I kept wanting to like the production more than I did. Directed by the more typically astute Derek Campbell, the production loses energy, however, in a flatness of presentation. There is little contrast between the pairs of characters, and the performance trudges along at a monotonous pace.

This becomes most frustratingly apparent in scenes of simultaneous staging in Act Two, performed on the uninspired “set design concept” by Meghan Raham. The dynamism of the arena stage at the Andrews Theatre is inexplicably sacrificed to the foreshortened literal staging of a stylized set. The cumulative result is clutter.

The production becomes heavily sentimental rather than bitingly ironic or insightful; maudlin rather than tragic.

Still, there are flashes of fine acting and isolated scene work to enjoy. Ever reliable Brendan Powers, Michael Providence, Guy Balotine and Christian Brandjes are once again very strong. Jeffrey Coyle adds to a list of memorable performances that have been accumulating quite rapidly over the past year. Steven Dawson and Joe Wiens similarly provide real characters with moments of compelling reality. If only the production as a whole added up to the sum of its parts.

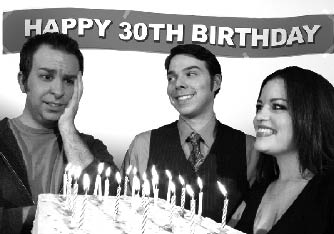

TICK, TICK…BOOM!

I had never seen Tick, Tick…Boom!, the other musical by Jonathan Larson, author of Rent. I was happily surprised at what a delight it is. The songs are wonderfully cynical and funny. Best of all, the show—about a struggling young composer watching his friends become successful as he approaches his 30th birthday—plays perfectly into the talents of the MusicalFare company.

Louis Colaiacovo, Michele Marie Roberts and Marc Sacco are perfection. Choreography by Kathy Weese is clever and moves the action briskly. Michael Hake’s expert musical direction is fueled by the strong voices of the cast. The direction is among the best Randall Kramer has ever accomplished.

I really loved it.

People should go see it.

WILD WOMEN DON’T GET THE BLUES

The onstage appeal of Mary Craig is magical. She brings a special allure to every performance and dips into a well-honed bag of tricks at will. In Wild Women Don’t Get the Blues, a revue of songs associated with great (mostly) African American singers of the 20th century, she pulls out all the stops.

It’s a whirlwind tour, taking us to Ida Cox (from whom we get the title song), Ella Fitzgerald, Lucille Hegamin, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Alberta Hunter, Etta Jones, Eartha Kitt, Carmen McRae, Ma Rainey, Nina Simone, Bessie Smith, Dinah Washington, Ethel Waters…you get the idea. Mary Kate O’Connell has conceived, directed and written the piece—presumably with Craig’s active involvement; the selections are very engaging and suit the singer very well. Craig establishes an easy repartee with her accompanist, Dan Schroeder, who has favorites of his own.

The show is best when the Craig persona is at its most casual and she seems to give actual personal recollections of what the singers mean to her. It drags in burdensome fashion when she reads the Cliff notes of each singer’s career from a memory book, or when her comic bickering with Schroeder feels like forced stage business intended to fill the time.

Craig is a notoriously spontaneous performer, and all of her shows grow in performance. One hopes that she will increasingly abandon the written text and flow with the music. More than the great ladies of the blues, we want to see Mary Craig.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n10: Imagine a City With No Police (3/8/07) > Theaterweek This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue