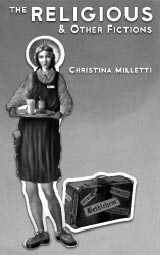

The Religious and Other Fictions by Christina Milletti

by Ted Pelton

The short story is a genre that may well be said to be in flux these days. Slick magazines which used to have stories as part of their regular formats have been phasing them out in recent years, and book publishers are less likely than ever to publish debut collections, with readers said to be more interested today in things that have “actually happened.” But on another part of the terrain are the legions of practitioners of the new and increasingly popular form known alternately as “flash fiction,” the “short-short,” “sudden fiction” and the like. These practitioners have been influenced by the plethora of new venues for fiction available via the internet, a medium less friendly to the traditional-length story, encouraging works which can appear in their entirety without much scrolling down the page. At the same time, flash fiction more and more frequently is practiced via an aesthetic merging with the prose poem, its writers eschewing the complexities of interwoven plots for those arising from the more compression-related techniques of image, language-play and indeterminate resolutions.

A collection like Christina Milletti’s The Religious and Other Fictions testifies to the continuing vibrancy of short fiction when undertaken by a virtuoso artist aware of all of these contemporary problems and directions, and more. Milletti’s fictions demonstrate a masterly range of effects, mixing flash fictions with more extended, ambling interpretations of the form and regularly employing surrealistic plot maneuvers that resist predictability at every turn.

A case in point is the shortish “Parcel Post.” In it, a woman arrives home to find a Post-it note on her door announcing the attempted delivery of a package. Not knowing from whence such a delivery might be coming, but tantalized by the possibility of a surprise gift, she leaves instructions for delivery, but the package is delayed again and again, with more Post-it notes forestalling the inevitable. In a more conventional execution, we would expect increasing frustration from the protagonist and, after a sufficient build-up of tension, eventual confrontation with the delivery person, post office, or some other logically deducible stand-in. Instead, Milletti’s story unhooks itself from the quotidian altogether and the notes themselves take on transformative properties of imagination for the woman. The result is a magically symbolic meditation on the wonders of imagination, rooted in possibility, “a fairer House,” as Emily Dickinson once told us, than (logical, predictable) prose.

An even shorter piece, “I Cook Every Chance,” shows Milletti to be an adept in the flash form as well. Here, the loss of common objects in the Kaspar household mutates first into surrealistic impossibility, with boys losing their books in the air of a bouncing school bus and then themselves going missing as their parents sit down to dinner. But by the time we arrive in the middle of the second page, we have entered a new space entirely, where narrative time has become a rich soup of memory, loss and the perishing even of souvenirs.

An uncanny experience attends the reading of these pieces. Milletti is able, in many of the stories, to have the various parts cohere, as it were, in the moments after the story has concluded, like the video of an explosion played backwards, constituent parts rushing together into an unexpected whole. Such is the case in “Sweetbreads,” one of the longer pieces, where the artist son of a small-town butcher, who specialized in supplying a nunnery with organ meats, is stipulated by the execution of a will to take over the old man’s business. Again, memory and loss are thematically at play, and the expected climax—that the son will discover something ennobling through work in his father’s humble trade—is entirely bypassed. Instead, we get increasing complexities—memories of the boy’s school-age lover, now lost; associations between the materiality of meat and the spirituality of cloistered life. In the end, we are unsure not only what is what in the story, but who is who. And then, an unforeseen coherence arrives, like a visitation.

Christina Milletti reads from and signs her debut collection at Hallwalls, 7pm, Friday, March 23.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n11: Muddying the Water (3/15/07) > The Religious and Other Fictions by Christina Milletti This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue