The Meaning of Scribbles

by Albert Chao

In the board game Pictionary, one rule applies: Speak only through drawing. Each player, whether gifted with the artistic hand of Leonardo da Vinci or that of a four-year-old, is allotted an hourglass of sand to produce scratches and scribbles to convey an idea.

Similarly, architects and artists use drawing in the design process as a tool to express ideas. Drawing Architecture, an exhibition of more than 50 drawings from the L.J. Cella collection, is currently on display at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. The exhibition features the drawings of contemporary architects and artists, from Frank Gehry to Modernist master Richard Neutra. The drawings range from scattered thoughts across a page ripped from a sketchbook to highly detailed architectural renderings. Each drawing is a look at different techniques in expression. The exhibition explores the process of design, rather than the final building form.

Contemporary Slovenian architect Marjetica Potrc’s Parallel Cities is a series of drawings that describe her approach to architecture. She uses simple, whimsical techniques reminiscent of the style of illustrators for children’s books. In her drawings, bold colors distinguish basic components; the hot pink of the “new” built form contrasts the gray drab of “old” architecture. Through these simple techniques, she articulates clearly her ideas of how to integrate the “old” and the “new” in what she defines as “Parallel Cities.” Potrc’s drawings, unencumbered with heavy jargon, speak invaluably of her response to this particular contemporary issue in architecture. In this way, her drawings spawn discussion of design in cities today rather than describe contemporary conditions.

Drawing also is a tool for sharing ideas before the installation or construction process, as demonstrated in contemporary American sculptor Terry Allen’s Music Forest. Allen imagines a symphonic forest with hidden speakers wired to trees. Instead of human musicians, each tree is a musician. A person activates the symphony by walking through the forest. The detailed pen-and-ink drawing speaks of the complex issue between the natural and the artificial. He challenges the relationship between architecture and landscape through a fantastic imagined installation.

Richard Neutra, the Austrian-born Modernist architect, also engages the landscape within his drawings. His highly rendered pastel perspective drawings of Kronish House in Beverly Hills, California, completed in 1953, are vibrant and animated. In this series of drawings, the house becomes the backdrop to nature, where trees, shrubs and flowers are charged with the energy of large, moving creatures and a blob of dark teal-blue sky that resembles the deep blue waves of an ocean. The Kronish House drawings allude to Neutra’s ideas on the integration of landscape and architecture. Though these drawings are more refined, they are still powerfully expressive.

In contrast to Neutra’s vivid visual descriptions of nature, contemporary artist Robert Irwin draws a more subtle portrait of nature. Irwin, originally an Abstract Expressionist painter, pursued installations that explore space and light. The series of drawings for Dia Beacon’s West Garden display a beautiful and meticulous color pencil drawing. The hard-lined drawing technique of the trees mimick that of the metal grates of the fence and surrounding architecture; nature becomes part of the constructed form. Another detail easily overlooked are the bright color studies dotted along the bottom of the drawing; conscious of his drawing materials, Irwin experiments in quick color studies before applying his techniques to the final drawing.

Vito Acconci, an influential conceptual artist who also works in architecture, is another featured artist. It is exciting to see his work materialize in architectural form. His series of concept drawings follows the development of an idea from sketch to form. The viewer walks through a time frame of each stage of idea development. The first stage presents a seemingly random scrawl of bubbles. The following stages consist of a more defined drawing of form. The pieces again are redrawn in a computerized collage that creates a rendered realistic space. It is one of the few pieces in the exhibition that engages contemporary drawing techniques with new computer technologies.

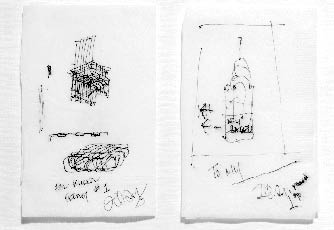

Frank Gehry’s ink drawings are the most quick and most fleeting of studies in the exhibition. In New York Bagel Shop, Los Angeles, scribbles of ink on napkins bring to mind the classic scene when inspiration hits and must be immediately transcribed to anything nearby—in this case, a napkin. Or we can imagine that the drawing was done during lunch with a client, and Gehry had to express his ideas quickly. Either way, these scribbles are an important means both of recording and presenting ideas, not arbitrary or inconsequential. In addition, the drawing begins to relate back into his design process, as can be seen in his other drawings for the Whitney residence or the Peter Lewis Residence, where form begins to emerge from a mess of doodles. His drawings are quick, free and highly controlled scribbles. Similar to looking at the paint splatters of Jackson Pollock, the eye constantly refocuses in a search for form.

Daniel Libeskind’s World Trade Center Scroll is a large and dynamic pencil-on-ink drawing on paper. Libeskind, winner of the 2003 competition to rebuild the World Trade Center site, generates great intensity and movement within the drawing by using heavy, quick marks. The drawing presents important process information for the design for the World Trade Center site—it essentially comprises notes on various elements, including site, context and form. The architect continuously pulls inspiration and ideas from this drawing when designing. This easily overlooked aspect of design is an essential part of the exhibition.

Other architects and artists in the exhibition include Lawrence Halprin, Richard Gluckman, Chris Burden, Kenneth Price, Richard Meier, Walter Jean Hood, Eric Owen Moss and Steven Holl. The exhibition was curated by Albright-Knox Associate Curator Claire Schneider and Brian Carter, Dean of University at Buffalo’s School of Architecture and Planning.

In collaboration with the Albright-Knox and the UB School of Architecture and Planning, internationally renowned architect Daniel Libeskind speaks at the Albright-Knox on Thursday, October 4 at 5:30pm. A subsequent lecture by Cella, Schneider and Carter will take place on October 19. The exhibition will be on view until January 6.

Libeskind has completed numerous civic projects including the Jewish Museum in Berlin, new buildings at Denver Art Museum and Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum. He has taught and lectured worldwide, including as Frank Gehry Chair at the University of Toronto. Libeskind was also a virtuoso piano musician before he began his studies in architecture.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n39: Into the Biennial (9/27/07) > The Meaning of Scribbles This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue