Into the Biennial

by Becky Moda & Eric Jackson-Forsberg

Big Orbit Gallery

Beyond/In Western New York at Big Orbit Gallery features two contrasting, video-based installations. Deirdre Logue’s Rough Count is a multi-channel installation documenting a seemingly simple act: counting. A year ago, Logue embarked on a sort of OCD performance project—to count all the pieces of confetti in a bag, then re-count them, with the goal of reaching exactly the same number each time. The installation documents this project through nine monitors installed in a grid, each showing a different attempt at counting. The cacophony of the overlapping sound from these multiple attempts makes it impossible to follow along and soon drives the viewer to distraction. The installation also includes two framed scratchpad pages with multiple tallies covering them—apparently, Logue’s informal, graphic record of progress and defeat in her ongoing campaign. We soon realize that “rough count” is an ironic title; the process is certainly hard on the counter, but the count is anything but rough. Logue’s text indicates that the work is “dedicated to the infinite and the endless.” But it is also about human failing and frustration in not being able to reach the infinite or even quantify a small portion of vastness in something as non-threatening as a pile of paper disks.

The installation by Sylvie Bélanger, Des fleurs pour décorer, creates a detailed environment within the Big Orbit space that reflects the spirit of the expansive, Beyond/In biennial in a microcosm of the group show concept. The installation actually incorporates the work of several video artists and designers, all (including Big Orbit Executive Director Sean Donaher) profiled in a catalog displayed within the space. Drawing on familiar tropes of the model housing unit, home-staged salesroom (think IKEA’s urbane settings) and trade-show booth, Des fleurs pour décorer invites the visitor to “be part of the 21st century,” where living space will be infused with customized video art and design for everyone (to steal a tag line from Target). Within this synthetic, showroom environment, visitors—viewers? consumers? prospective buyers?—may interact with various framed video screens, changing their display with the click of a mouse.

One shrine-like area features a menu of video shorts by various artists, with banal titles (and content) like Iceberg (lettuce), Duck and Tourist—video that lends itself to being hung on the wall as a sort of digital decoration. The coffee-table books displayed in the space—The Invisible in Architecture, Art Now, etc.—are all mock-ups filled with blank pages, as if to herald the death of print media and present the book as decorative object only. The dining area of the installation features a virtual vista onto a bucolic garden scene. In the lounge area, visitors can sit and manipulate two large monitors to select familiar genres of video-as-painting—portrait, still life, landscape—each an ironic take on the type it represents. This interactive environment brought to mind the home-of-the-future visions of Ray Bradbury, who describes a condition in Fahrenheit 451 where living room walls are merged with video monitors such that inhabitants are surrounded by planes of inescapable imagery. Bélanger’s vision of home décor is not quite so extreme, but points the way to a future where media, art and entertainment are woven into our environment in a fully integrated, infinitely mutable habitat. All the while, the gritty, dark envelope of the Big Orbit space floats overhead, reminding us that this is a temporary fantasy of a digitized utopia.

—eric jackson-forsberg

Buffalo Arts Studio

Bryan Hopkins’ oddly beautiful porcelain pottery/sculptures at Buffalo Arts Studio are from an ongoing series called Dysfunction. The meaning behind the title of the series in part relieves our bewilderment about pieces named Vase or Bowl that literally won’t hold water. Hopkins questions the ceramicist’s allegiance to functionality. But it’s the very essence of function that Hopkins provokes us to consider. There’s a whole mental process of confusion and reevaluation when these usual applications of ceramics as containers are called into our minds as we look at objects that could just as easily be architectural models from a colorless planet. In Hopkins’ hands, porcelain is not the smooth, symmetrical signifier of opulence we know it to be; it is a versatile medium of variegated shape and texture. These dysfunctional containers are flawed, perforated, waved or pimpled, with glazed and matte slabs of contrasting patterns stretching to meet, often at differing heights. The inherent translucence and fragility of the material lend an otherworldly pallor and limpid silence to these coolly organic creations. Unfortunately, the odd placement of these semi-silent pieces was ill at ease with the visual cacophony of another artists’ work in the gallery.

—becky moda

Open Columns—Rendering of 2 States by the team of Laura Garófalo and Omar Kahn is a kinetic work that connects architecture, sculptural installation and cybernetic systems. Two net-like “columns” composed of composite urethane elastomers respond to invisible factors in their environment to assume their shape. The installation includes two carbon dioxide monitors—one that reads ambient levels in the space and one that visitors can deliberately activate—tied to motors that raise and lower the flexible forms according to levels of the common gas in the area. These are accompanied by a small working model showing a hall populated by such columns, demonstrating the application of this strangely sentient architectural system on a larger scale. Rather than promoting some new structural system, Open Columns is a didactic model for the complex relationship between human beings, the environment, and technology. Carbon dioxide, the major greenhouse gas that promotes global warming, is used as the factor that literally shapes the environment; the concentration of bodies in the space causes the forms to expand or contract, providing a provocative metaphor for the emergent crisis of global warming. This metaphor is surely too subtle for those who would still call for “further study” of the crisis, but for the rest of us it provides a unique illustration of our leading role in shaping both natural and built environments.

Environmental balance and material intervention is also behind the paintings of Kara Daving. These luminous, beguiling images of various species of jellyfish are powerful in and of themselves, but a new layer of meaning lies in the unique material the artist paints on: plastic bags. In her choice of support, Daving raises our awareness of this ubiquitous object, one that all too often makes its way into rivers and oceans. These paintings set up a self-reflexive dialogue between materials, meaning and technique. Daving’s deliberate drips of paint resemble the hanging tentacles of many species of jellyfish, while the ragged edges and gossamer surface of the bags mirror the miraculous bodies of the creatures depicted. Daving’s paintings may be experienced on multiple levels: as aesthetically rich images, as unusual explorations of material, and as elegant, thoughtful essays on humans’ environmental impact. Next time the supermarket cashier asks me that seemingly philosophical question, “is plastic okay?” I might think of used bags floating in the ocean like lifeless sea creatures—and I might think twice.

—eric jackson-forsberg

Carnegie Art Center

Seen from the front door of the Carnegie Art Center, Katherine Sehr’s drawings don’t look like drawings at all, but rather like prints of simple, paired squares of muted colors. Upon closer inspection, however, they reveal themselves to be something entirely different—large, frenetic, scribbled testaments to compulsive, repetitive motion. Sehr’s freehand squiggles are amazingly uniform in pattern, seemingly without variety despite the large scale of the pieces. The effect is one of controlled chaos, an electric, jangling convolution, framed and strengthened by perfect squares, which are entirely filled but never transgressed. Of particular interest is one piece in which Sehr unmasks her method, leaving one of two squares largely unfinished, a few tendrils of her curling tremors wisping suggestively into negative space. In fact, what you see in Sehr’s pieces is mostly space—like the space in and between the atoms that comprise our bodies and all of the objects around us—but it is the smaller something that is alive, that informs, defines and dominates, until the larger void is nearly beyond perception.

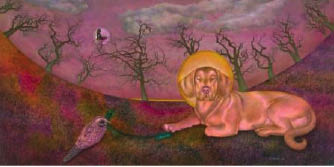

Jacqueline Welch allows her love of animals and her Catholicism to combine in startling, unorthodox ways in her work. Animals—mostly dogs—take the place of the human form as the central focus of her paintings, and are not only respected as an equally valid subject, but literally sanctified. Each piece is titled a “Patron Saint” of some idiosyncratic, mostly embarrassing trait of the contemporary human condition: the Paxil Patient, the Lonely Heart, the Nearsighted, the Flat-chested, et cetera. She emphasizes this religious theme by incorporating elements of Renaissance Christian paintings: These pieces are painted on wood, some in the form of triptychs, and each sanctified figure wears a solid halo. Other icons of various origins float in the ether, connecting natural, mystical, and absurd motifs. The wood adds an organically linear texture to the paint, while darkening colors, producing a rich, time-worn effect. Welch employs a grab-bag of disparate devices, including cartoon-derived thought and voice bubbles, to great comic and sometimes political effect. The divine canine in Patron Saint of the Inarticulate utters three well known Bushisms (e.g., “They misunderestimated me”), while, in the background, our beloved president and VP stroll by, grinning a little too broadly. It’s all a bit strange, but the halos seem surprisingly appropriate on Welch’s exalted canines. No human, after all, could possibly be as innocent, faithful or pure of heart as the average dog.

—becky moda

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n40: Failed State Diary (10/4/07) > Into the Biennial This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue