Before All Memory Is Lost

by Bruce Fisher

The Polish story of survival in Buffalo after Hitler and Stalin

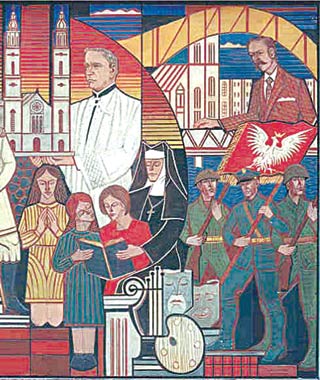

Deep in a dark recess in Buffalo’s City Hall is a terrifying piece of art made by the same Polish exile who created the Calasanctius mural. Jozef Slawinski’s hammered-copper bas-relief commemorates the place, the event, the process, the unimaginable suffering that the Poles know as Katyn.

Everybody has heard of Picasso’s Guernica, that terrifying huge canvas at a Madrid museum that portrays the German bombing of a Basque village during the Spanish Civil War. Everybody in the world should know of Slawinski’s abstract piece on the Soviet massacre of more than 16,000 Polish officers, elected officials, nobles, and intellectuals in the Katyn forest during World War II.

Had it not been for the late mayor Jimmy Griffin making a political gesture to Buffalo Poles, then not even Buffalo would know about Katyn.

It’s as if history has been privatized. Just as Slawinski’s Katyn is hidden away in an alcove few visit, the stories of a generation of as many as 20,000 immigrants to Buffalo have never become known beyond the whispered conversations of survivors. On the border between Buffalo and Cheektowaga, there are hundreds of stone monuments to members of the Polish army-in-exile who came to America, specifically to Buffalo, and who lived out the remainder of their lives in the hope of returning to their homeland, but while here created a complex legacy that literally reshaped our collective landscape.

Andy Golebiowski and a small group of volunteers formed the Polish Legacy Project to try to gather up some of the stories of the Polish DPs. DPs were the “displaced persons” who survived the German death camps, including Auschwitz and Buchenwald, where so many of their Jewish and Christian countrymen were murdered. The DPs were also the survivors of the German forced-labor camps and farm-labor slavery, people who then found themselves stranded in Allied zones at war’s end in 1945. The DPs were also thousands of Polish military men, like the legions who fought in Italy, who knew that Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt had decided the fate of their country at the Yalta conference in 1945—which was to leave Poland in the Soviet sphere of influence, and leave them in need of a place to go that wasn’t going to be ruled by the Russians who had also slaughtered, deported, or brutalized their countrymen.

Golebiowski, a Buffalo native who works as a camera operator for a TV news station, himself knows many of these stories. His mother, who was seven in 1939 when the war began, was living on a farm when the Germans rode into the nearby town of Rokitno and massacred all the Jews there. She tells how her Catholic parents gave refuge to two Jewish children who had somehow survived the shtetl liquidation, and how the Nazis returned to their farm only hours before her father took those children into the woods to deliver them to the partisans, for the Nazis had threatened to burn their farm to the ground if they found any Jews hiding there. They searched. The children were gone. They burned the farm anyway. They were lucky: The Nazi penalty for aiding a Jew in Poland was death for the entire family.

Golebiowski’s mother can still tell how she came to America. His father, a prisoner of war who was forced to work on German farms, told his own harrowing stories, but they died with him in 1999. Many of the people who came to Buffalo have died, taking their stories with them. In the Saint Stanislaus Cemetery on Pine Ridge Road, gravestones in a special military section are marked with the names of regiments and the briefest of notes about war-time experiences. These notes form a succinct code of service, and of suffering. “Sibyr,” say many of them, a brief reference to the horrors of young men and women who were deported to Siberia. “Auschwitz” is carved into several of these crosses, reminding us that three million Christian Poles died during the same period that three million Jewish Poles were murdered. “Monte Cassino” is on several, a note about the Poles’ unheralded capture of Sicily before the armies of Patton and Montgomery won glory there.

The world the Poles made here

They began arriving after 1948, when President Harry Truman signed a special displaced persons immigration bill, which he criticized for being so insufficient a gesture that he called it “inhumane.” Americans today can be forgiven for having forgotten how immense the destruction of World War II was—because that cataclysm ended 65 years ago, and since then we have seen Vietnam, Central America, the Rwanda genocide, the Bosnian massacres, Iraq, and more.

The story that will unfold in the Polish Legacy Project’s conference October 3 and 4 here in Buffalo, though, is partly about the local impact of the largest forced migration in history.

Everybody more or less knows about our great 19th-century immigrant stories. Joey Giambra recently made the documentary La Terra Promessa, about the Sicilian story. Irish-Americans succeeded, after many years, in erecting a memorial to the Irish famine of the 1840s, in which hundreds of thousands died, and which led to the mass exodus of the Gaeltacht. There has even been a film made of the pre-1920s Polish migration.

But the thousands of Poles who found refuge here after World War II are a different, separate, largely untold story.

These were not the unlettered peasants imported by Gilded Age industrialists to work the mines and factories. Many of the displaced persons were educated, because Poland in the years after World War I had broadened the reach of its schools. Many DPs arrived knowing English, especially those who had been in the military in Britain or in British-controlled territories in the Mideast. Some had been among the 1.5 million Poles who had been exiled to Siberia or to Central Asia by Stalin; there are, or were, Poles in Buffalo who had toiled in cotton fields in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan until they made their way out.

And their presence in Buffalo was not without friction, even in a generally welcoming Polonia.

Educated refugees from Poland’s 20th-century cities arrived in a city whose Polish population was two or three generations distant from Poland’s 19th-century farms. The new arrivals spoke a different, more modern language, not the frozen-in-amber antique from their grandparents’ day, which was even stranger for all its Americanisms. The DPs were not much interested in that non-Polish musical phenomenon so beloved of American Polonia, the polka. College-educated people from Poland had little in common with factory workers clustered in neighborhoods around the Broadway Market. Some have observed that the newcomers were not at all like the bar owner described by Verlyn Klinkenborg in The Last Fine Time, who was happily becoming more and more American all the time as the 1950s became the 1960s. Though grateful to America for providing refuge, these migrants were not interested in being American: They were Poles.

They formed Polish-language academies, the “Saturday schools” to which they sent their children so that their next generation would be fluent in written and spoken Polish, conversant with Polish history, aware of Polish national holidays, and part of the thousand-year continuity of Polish culture. They did not feel bound by any particular neighborhood, though the parishes and Polish-American sponsors welcomed them. Their neighborhoods were back home, and until they gave up the dream of returning, the focus, for many, was not North America but Europe.

The urgent task

The children of the DPs are themselves now in their 40s, 50s, and 60s. If the DPs themselves are still alive, there is not much time in which to do the job of “rescue” or “salvage” collecting.

Thus the urgency of the conference. Strolling the rows of crosses at the Polish Veterans’ Plot at St. Stan’s Cemetery, one senses the urgency-cognizant of the fact that in five years, when the 75th anniversary of WWII is commemorated, there may be no one left who can give a firsthand account of life then.

The Polish Legacy Project’s mission is to record and to share the untold stories before they join all the other undocumented stories at the cemetery. The PLP is fighting against the clock, trying to make up for 60 years of silence. Unlike the stories of the Holocaust, these stories of survival, suffering and heroism largely do not exist in the English language.

Work has begun on videotaping survivors’ accounts, and in collecting photographs and artifacts of the Poles’ long journeys to Buffalo. Golebiowski and the other organizers hope that the conference will serve as a critical spark to a wider engagement on the part of interested people and institutions, and perhaps give survivors new-found courage to talk about experiences that have either been private, or about which they’ve kept silent.

Visit www.PolishLegacyBuffalo.com for conference details.

Bruce Fisher is visiting professor of economics and finance at Buffalo State College, where he directs the Center for Economic and Policy Studies.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v8n38 (week of Thursday, September 17, 2009) > Before All Memory Is Lost This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue