Next story: Scorecard: The Week's Winners and Losers

Seven Days: The Straight Dope From the Week That Was

by Buck Quigley

Coordination Exercises

Last Thursday North District Common Councilman Joe Golombek won the endorsement of the Frontier Democratic Club in his primary challenge at Assemblyman Sam Hoyt. That’s an important win for Golombek, though not completely surprising: The Frontier Democrats backed Golombek when he first ran for Common Council, against an incumbent, in 1999.

Golombek was present to ask for the endorsement and answer questions. Hoyt was not; he was in Albany, where legislators still have not passed a budget. (Sixty-three days late and counting at press time.) Hoyt was represented at the meeting by Jeremy Toth, a veteran of Hoyt’s office and his campaigns, and Toth gamely took a shellacking for his boss: The crowd hammered Hoyt for his proposal that educators undertake a voluntary wage freeze to help cut state expenditures; they asked if he’d forgone his Albany per diem while suggesting others to take furloughs; they rolled their eyes at the budget’s perpetual lateness; they tarred him for his continued support of Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver; they asked why state government had failed to anticipate and forestall the state budget crisis.

In short, they labeled Hoyt with all the weaknesses and failures of Albany, which is pretty much the hand you’re dealt if you’re an 18-year incumbent. One audience member asked if the candidates were in favor of IDA reform. Golombek said he was. Toth volunteered that Hoyt had helped to write an IDA reform bill that was working its way through the legislature. Maybe the young man had read it? He had. “I don’t like it,” he said. There was no winning that room for Hoyt that night. The anti-incumbent mood has never been stronger, and Golombek is doing a good job riding that train.

Toth did score some points when Dennis Ward—a commissioner on the Erie County Board of Elections, and an ally of Hoyt and Democratic Party headquarters—asked Golombek whether he would seek or accept the support of Sabres’ owner Tom Golisano, who spent about a half million dollars trying to unseat Hoyt two years ago. Golombek replied that he would accept Golisano’s money if it was offered, but that he had neither met nor spoken to him. “And I would be willing to work with Mr. Golisano on issues that matter to me,” he added.

Would Golombek reject independent expenditures on his behalf? The sort of expenditures that Golisano and his political director, Steve Pigeon, had made on behalf of Barbra Kavanaugh two years ago?

“I would do what is legal,” Golombek replied.

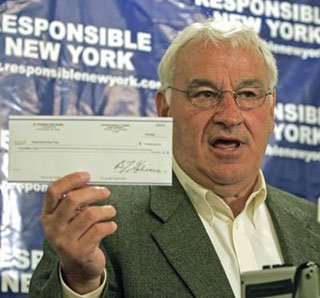

What’s legal is a tricky question, of course: It would be illegal to reject independent expenditures from a group like Golisano’s Responsible New York, because rejecting them would imply that you knew they were going to occur, which would imply coordiantion between the campaign and the independent committee. And that’s a felony.

“The only phone call I know of to go from a candidate in the 144th Assembly District to Mr. Golisano looking for support was Sam Hoyt,” Golombek replied to Ward.

Both Ward and Toth wanted to know how Golombek knew Hoyt had called Golisano, and Golombek indicated he’d heard a voicemail Hoyt had left on the billionaire’s cell phone.

Toth, an attorney, pounced. “Somehow Joe got the voicemail from Tom Golisano’s cell phone,” he said, pacing as if in a court room. “There’s a crime in New York State election law called coordination. It’s a felony to coordinate expenditures with a campaign to avoid campaign finance law. It happens all the time in this region with Steve Pigeon, and it’s going to happen again this year.”

Toth pointed across the room accusatorily. “I don’t know how he got the voicemail, but I would suggest that there would have to be a coordinated effort to get Joe Golombek the voicemail from Tom Golisano’s cell phone.”

Toth reminded the audience that in 2004 Erie County Executive Joel Giambra, working with Pigeon, had quietly spent many tens of thousands of dollars on Golombek’s unsuccessful campaign against Hoyt. The New York State Board of Elections determined, 18 months later, that the Golombek campaign had acted improperly, but Toth said Golombek still would not admit that Giambra had supported his candidacy.

“I have been attacked unmercilessly for receiving Giambra money in 2004,” Golombek countered, and blamed the attack on his audacity in challenging an incumbent. “[The Democratic Party] is an incestuous group that is more concerned with reelecting people to Buffalo, to Erie County, to Albany, regardless of whether they’re doing a good job or a bad job. They want to control things.”

True enough, but Golombek’s not exactly the new kid on the block, and Pigeon and his wing of the local Democratic Party—who will indeed back Golombek—are certainly as interested in control as anybody.

And lost in Golombek’s exasperation with the party system was an answer to Toth’s question: Who gave Golombek a voicemail that Hoyt had left on Golisano’s cell phone?

Charter Party

On Friday, the NYS legislature voted in favor of more than doubling the number of charter schools in the state—from 200 to 460—in an attempt to secure hundreds of millions of dollars in Race to the Top funds from the federal government. New York finished second to last among the 16 finalists for the money back in January, but this time New York City mayor and charter school advocate Michael Bloomberg was able to convince lawmakers to lift the cap, especially in the Big Apple where nearly half of the new charters must be located.

The state Board of Regents and SUNY will split the duties of issuing charter school permits.

The charter cap in New York has been characterized as the negative determining factor last time around, but if you watch the presentations given by winners Delaware and Tennessee, and contrast their performances with the one given by New York, you might disagree. Those states, for starters, thought the presentation was important enough to merit participation by their governors in front of the judges. Not so with New York. You can see for yourself on YouTube.

Union spokespeople worry that lifting the cap in cities like Buffalo and Albany will lead to a glut of charters, siphoning enrollment from traditional schools. Concerns have arisen that charters will simply turn problem students back to the traditional schools. On top of that, standardized test scores can now be used to evaluate teachers, leading to more training or even termination by a school district.

At the beginning of May, Buffalo school administrators got the date wrong for the state math test—surprising thousands of students on the night before the test with an automated call home to their parents, warning them that the tests would be given the next day. Other school districts across the state knew the correct date of the test six months in advance. Superintendent James Williams dismissed the gaffe, saying students have been preparing all year. “It’s not a big deal,” said the superintendent, who won a contract extension one week ago that will make him the longest serving Buffalo school superintendent since Eugene Reville.

We’ll see how those math test scores look when they come back, and how they are then used to evaluate teachers and kids.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > 20th Anniversary: Week of Thursday, June 3 > Week in Review > Seven Days: The Straight Dope From the Week That Was This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue