Next story: Mayor Opens 311 Line to Inner Harbor Development Ideas

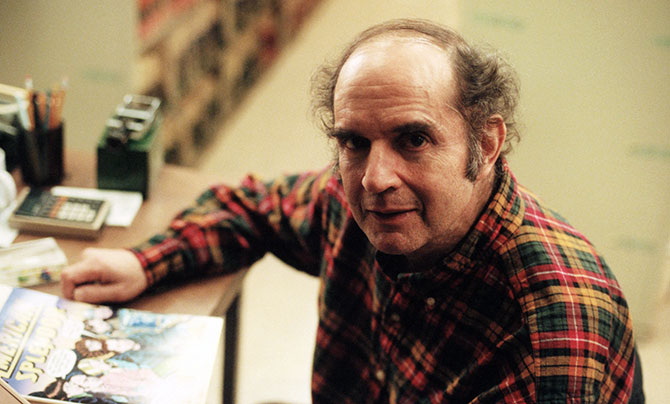

Remembering Harvey Pekar

by Tim Madigan

“Comics are words and

pictures. You can do anything

with words and pictures.”

—Harvey Pekar

Harvey Pekar, author of the famed graphic novel American Splendor, died on July 12th, aged 70. Best known now for the film version from 2003, American Splendor began in 1976 as a self-published yearly comic detailing Pekar’s life as a file clerk at a Cleveland hospital. It is a chronicle of his life: his boyhood, growing up as a “greaser” in the 1950s; his varied relationships with women and his eventual marriages (he’d been wed three times and each wife puts in an appearance in Splendor issues); his reflections on politics, literature, jazz, work, and life in general.

Pekar was a down-to-earth guy who tried to record things as they really happened. He was reflective without being preachy. In his story “Rip-off Chick,” for instance, he told of his on-again, off-again relationship with a woman he described as being “basically a worthless person,” then adds, “Dig me, casting stones.”

One could never accuse Pekar of pandering to his audience. He did nothing to spruce up the often grim realities of his day-to-day existence. Many of the stories dealt with his money woes, his anxieties about growing old, his health issues (including several bouts with cancer), and his tendency to say the wrong thing at inopportune moments.

Yet for all their apparent harshness, one had to admire Pekar’s attempts to show life as it really is: for the most part unglamorous, often tedious, but nonetheless worth living. His stories remind me time and again of Samuel Beckett’s famous words: “I can’t go on/I’ll go on.” It is the meaningfulness of simple pleasures which really come across in these tales. In one of them, Harvey—who portrays himself as a diehard cheapskate—comes across a secondhand store which sells good shoes for 50 cents a pair. He’s in heaven!

Much praise is also due to the various artists of these works, for these stories were all collaborative efforts. Pekar—who couldn’t draw—wrote them, then worked closely with the men and women who depicted, through their artwork, his autobiographical texts. Probably the best-known of these artists is Robert Crumb, creator of Fritz the Cat, Mr. Natural, and other famed underground comics and recently the creator of a comic rendition of the Book of Genesis. The two first met in Cleveland in the 1960s, and it was Crumb’s wild versions of a nervous, bug-eyed Pekar that first gave Splendor its prominence.

I first met Harvey back in 1985. At the time I was an undergraduate student in philosophy at the State University of New York at Buffalo. As a child I had been a big comic book fan, but had long since put them aside and felt I had given up such childish things for good. My friend Craig Fischer, then an undergraduate student in English at the same institution, convinced me that comics were worth reconsidering, and that several important works were expanding the field in ways previously unimaginable. When Craig showed me American Splendor, I was convinced that the comic book world could indeed develop narratives in a mundane but nonetheless exciting way. How could someone growing up in Buffalo, New York not love a work that dealt with stories about old cars not starting on a winter’s day? That was something I could truly relate to, and something I’d never before seen in a comic book.

Craig and I took several pilgrimages to Cleveland to meet the master. I well remember the first occasion, where we burst into his apartment—which was crammed wall-to-wall with record albums and books—holding up a six-pack of beer and offering to take him out to get an order of chicken wings. We were shocked when he told us he neither drank alcohol nor ate meat. Thus were our preconceptions shattered. He also told us at the time that he had been invited to appear on Late Night With David Letterman. This seemed to us a great opportunity to alert the world to his work, but Pekar astutely said that the only reason he’d been asked to come on was so that Letterman could make fun of him, and that instead he was going to come out and aggressively attack Letterman. It seemed to me that this was exactly the wrong thing to do, and I can well remember watching, with fear and trembling, the first appearance of Pekar on Letterman’s show. His strategy, it turned out, was spot-on—it was so unexpected, and so entertaining, that he appeared several more times, which itself became grist for the American Splendor mill, and led to some memorable television experiences.

I stayed in touch with Harvey, on and off, over the years. We mostly talked on the phone about avant-garde literature and jazz; he hated Ken Burns’ PBS series on the latter. I kept encouraging him to put together an anthology of his jazz criticism, but he grumbled that it would be too much work and not lucrative enough to be worth the bother. I also closely followed what seemed to be the quixotic efforts to get American Splendor made into a film. One memorable event occurred at a Toronto restaurant in the early 1990s, where I drove up to meet him and a potential producer. While standing around with a group of Pekar acolytes, Harvey burst into a profane diatribe about how the producer never showed up, and that it was all futile anyway, since nothing ever came of such meetings, and the guy was probably nothing but a lying jerk. Suddenly one of the people standing by said in a quiet voice, “I am here.”

It was the potential producer. The rest of us fell into stunned silence, and Harvey awkwardly put out his hand and said, “Hey, man, good to meet you.” I recall staggering out into the Toronto night, nonplused and yet happy to have witnessed a genuine Pekar moment.

A few years later, while flipping through Entertainment Weekly, I saw a still for an upcoming movie. “That looks like Harvey,” I thought, and then learned that it was actually Paul Giamatti, portraying Our Man. So a film was indeed made, and it very nicely captured the complexities of the Pekar world. When I called him up to congratulate him, Harvey said, “Well, we’ll see how it does.” After the film won several awards, and made Pekar the center of media attention, he told me, “We’ll see how much I’ll be talked about a year from now.”

And, as usual, he grumbled about how everyone thought the movie had made him a lot of money, which was not the case.

I last met up with Harvey about a year ago, when I stopped by his cluttered home to catch up on things. We wandered over to a hamburger joint and, even though I offered to pay, he insisted on picking up the check. “I’m doing all right, man,” he said. Most of all he seemed if not happy then at least immersed in work, which was probably the best thing for him.

I last spoke to him in April. I had arranged to bring him to give a talk at my school, St. John Fisher College, and he called a month or so before to say, “Hey, man, I completely forgot, I’m gonna be in San Francisco then.” With anyone else I’d have been upset, but Harvey being Harvey, I shrugged it off and was planning to bring him to town in the fall semester of 2010. Now all I have are the memories of my meetings with him, my Harvey Pekar bobblehead, and my dog-eared copies of American Splendor. It’s still difficult to think of him in the past tense, for he was a vital part of my life for 25 years. I wish he could have seen all the tributes to him, for I suspect he relished the recognition he did receive for making his life his life’s work. He was a genuine inspiration to me and to countless others who continue to see the extraordinary in the ordinary. Thanks to American Splendor, we can all better appreciate our own Pekaresque moments.

Tim Madigan teaches philosophy at St. John Fisher College in Rochester.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n32 (week of Thursday, August 12) > Remembering Harvey Pekar This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue