Deliver Us From Decay

by Jack Foran

Demolition and death, molding cakes and flaking canvasses: entropy and redemption at Beyond/In

The artists at least seem to be facing facts. In a region that used to be prosperous, but now the principal city of the region boasts to be third most impoverished in the nation, there’s lots in the Beyond/In Western New York biennial about death and decay. It’s a kind of unofficial theme.

Start with the daffy cake architecture display outside the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society. New York City artists Mark Dion and Dana Sherwood had local bakers produce cake models of some area architectural treasures, partly as homage to the buildings, partly to demonstrate the ravages of time on these confections over the course of the biennial, from September through December. As a kind of epitome accelerated version of the deterioration process affecting the actual buildings. The ones still standing, that is.

At last look, the confectionary buildings are not doing well at all. The cool weather has been a godsend, but most are in a state of advanced collapse. Decidedly unappetizing.

But credit where credit is due. Two structures still holding up remarkably well—and two of the most impressive recreations of their prototypes—are Henry Hobson Richardson’s Buffalo Psychiatric Center and Frank Lloyd Wright’s late lamented Larkin Administration Building. Both are by Dessert Deli.

Across the street, at the Burchfield Penney Arts Center, a small army of artists address the death and decay theme, throwing in another d-term, destruction, for good measure.

Three of these artists—Dennis Maher, Julian Montague, and Jean-Michel Reed—have previously worked together on an art project called Ecologies of Decay that considered urban decay as part of a life process, on the road toward urban regeneration.

Sound hopeful? But the focus of the work of all three artists is on the decay, destruction phase, without any real attention to the inferential regeneration phase. So be it. These are artists, not city planners.

Maher makes gargantuan sculptural conglomerates of building demolition site materials. Planks, plaster, plumbing, you name it, in completely chaotic array. A huge hanging globe of such deconstruction materials serves as a sort of centerpiece—literally and figuratively—of the collective Burchfield Penney Beyond/In installations. What’s more interesting are his photographic depictions of the jumble of demolition scraps that look like they’ve been processed through several iterations of some abstractive technique, leaving shadowy patterns that suggest some system to the madness. Which there is, in the sense that this disparate miscellany once existed and functioned as a system. (And given recycling, could conceivably again. Part of the inferential regeneration thing.)

Montague’s art focuses on the biological mechanism of housing deterioration, the vermin small and large—think termites in basement rafters, think squirrels nesting in eaves hollows—that are nature’s means for transforming architecture into compost. Montague’s exhibit includes a veritable insect zoo of critters pickled and dried in specimen bottles, and an encyclopedic presentation on where and how they inhabit our built environment uninvited and unwelcome (or is it we who inhabit their natural environment uninvited and unwelcome).

The encyclopedic information includes a number of books on insect infestations and the like that Montague has not just gathered but actually produced—they’re not actual books, but look totally actual, totally authentic—for the exhibit.

Reed takes photographs of house fires at night—Buffalo has a lot of these—that as images raise the aesthetic/philosophical matter of the sublime, and constitute instant housing demolitions.

Other Burchfield Penney artists doing death and decay works are Carl Lee and Kyle Butler. Lee makes speeded-up videos of actual housing demolitions, start to finish, documenting the fascinating work of the bulldozer claw tool, which looks a little and acts a lot like some of Montague’s wood-chomping vermin, but as macrocosm to the vermin as microcosm.

Kyle Butler’s paintings are about structural breaking points in the face of natural forces. Things fall apart when tornado winds hit them.

Across the street again, at the Albright-Knox, Sarah and Suzannah Paul’s extremely beautiful and evocative installation about the industrial past of Rust Belt cities like Buffalo (and implied post-industrial-period impoverishment) projects video of smokestack flaring (a process to burn off particulates and other flammable wastes from the emissions) against a curtain of smoke-begrimed windowpanes in unpainted (or long bereft of paint) sashes.

Also at the Albright-Knox, Joan Linder’s steady and straightforward look at human mortality consists of meticulous pen and ink drawings of cadavers in process of dissection at the UB Medical School. These drawings are about death and dignity. Affirming both. When death is a gift given.

A more complicated and tumultuous installation on human mortality is Kurt Von Voetsch’s autobiographical drawings and sculptural fabrications at the Anderson Gallery about his coming to terms (or not) with his cancer diagnosis and treatment. It says, among other things, do not go gentle.

Also at the Anderson Gallery are Rodney Taylor’s handsome paintings of trees in the unusual and particularly deciduous medium of paint and clay, which is intended to flake off—and is flaking off—the paintings over the course of the exhibition. The generations of men are as the generations of leaves.

Death is an iron law, of course. And then there is needless death, some of the artists are saying. For example, in the matter of hunting as machismo sport. Two artists make this point, Yasser Aggour at the Buffalo Arts Studio, and Adam Weekley in installations at the Castellani Gallery and Buffalo Arts Studio.

Aggour takes trophy hunting pictures typically showing the proud hunter supporting the head of his newly slain animal victim—both hunter and animal looking straight on at the camera—and by digital manipulation techniques removes the hunter. What seems at first glance to be straight nature photos of magnificent animals in the wild, caught off-guard as it were. Standard nature photography, in other words. But then on a closer look, there’s blood.

Weekley’s enigmatic sculptural and drawing works are strewn with the more enduring remnants—detached antlers—of deer killed maybe for the meat, but the antlers are the trophy part.

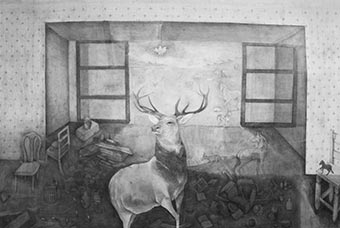

Also at the Castellani are Elizabeth Gemperlein’s post-apocalyptic visions of iconic animals triumphant amid human architectural ruins. But no humans in sight.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n46 (Week of Thursday, November 18) > Deliver Us From Decay This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue