Drawn From Life

by J. Tim Raymond

Portraits by Harvey Breverman at Daemen College’s Fanette Goldman Carolyn Greenfield Gallery

I first discovered contemporary painting in the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, coming up to the capitol city on a senior trip. Among the work by the relatively younger painters exhibiting in 1964 was a painting by a figurative painter, Harvey Breverman, a recent addition to the art faculty as a studio professor at the University at Buffalo, and the first with a postgraduate degree. Only a few years out of college and serving in Korea, Breverman had graduated from Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University) after a youth spent in the religiously cloistered environs of an Orthodox Jewish Brooklyn neighborhood, and had been invited to participate in the Corcoran’s 28th Biannual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting.

His eight-foot-high work of a single individual immediately had an impact on me. It was a self-portrait, titled Self-portrait as a Bal Korah, or Torah reader: Breverman posed in three-quarters view holding a canvas only barely visible to the viewer. He wore his army fatigues and a blue T-shirt. Realistically representational but in no way stopping there, it had a sense of a deeply personal observation, especially in the face and hands. It appeared extracted from experience and carried the artist’s emotion and insight. Displayed between the works of Edward Hopper and Rico LeBrun, his painting was chosen for the UB president at the time, Clifford Furnas, and hung in his office throughout two administrations.

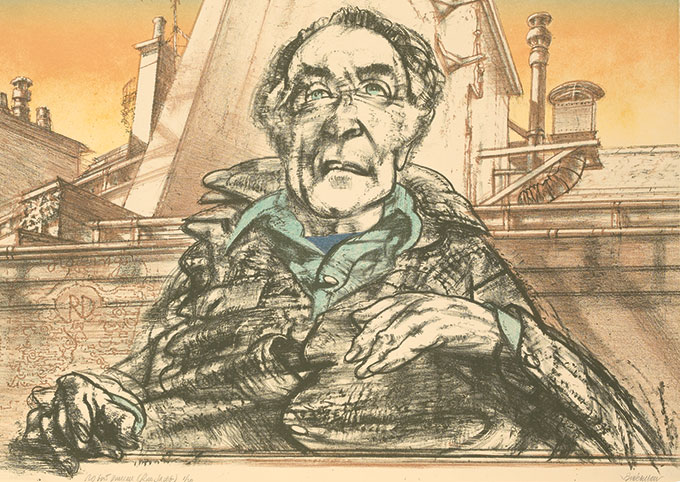

Breverman’s abiding theme is the existential dilemma, man alone among the many, a sense of the self—isolated yet infinitely multiplied, like figures in a reflecting mirror. Completed between 2004 and 2006, his lithographic studies, a limited edition of 20 by master printer Chunwoo Nam, illustrate five contemporary figures (most notably the late poet Robert Creeley) in typical faculty lounge poses, collegially relaxed. But Breverman’s figures are iconic structural edifices more than just portraits. Like Giacometti, he builds visual weight on the placement of form in a space, situating each person fixed yet fleeting, as if the figures are holding a place for the viewer, that they might change places and so identify with the universal humanity of his vision.

Two of Breverman’s late contemporaries, Edwin Dickinson and Lucien Freud, also found a challenge in depicting human relations in isolation, discord, frailty—interaction and disjunction creating connections and disconnections and raising questions in their work that only the viewer could answer and only for themselves. In Breverman’s candidly posed subjects there appear to be a kinetic energy, vestiges of breath, traces of intention, plasticity in the features exaggerating the appendages: Noses, ears, mouths, hands border on a kind of sublime caricature. His subjects rarely look out at the viewer directly, often remaining detached from environment and viewer alike, as if caught in mid-conversation or private meditation.

Surrounding the figures in his works are Breverman’s personal iconography of idiographic objects and symbols with which he creates a coronet around the figure in secular/religious tangents, reinforcing the sense of man in the inchoate era of the Holocene.

Drawn from Life continues through November 11.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n44 (week of Thursday, November 3) > Art Scene > Drawn From Life This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue