Can't Stop Reiman

by Jack Foran

Joshua Reiman’s work at Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center

In a talk in conjunction with the opening of the current show of some of his works at Hallwalls, artist Joshua Reiman said of his early work (but it seems to apply to his later work as well) that he was trying to tell a story, only didn’t know what the story was. (A respectable précis description of any true artist’s life and work, I would think.)

Whatever, it’s a funny story, satiric, and more than a little elegiac. And loaded with visual and verbal puns. And historical and art historical references, the latter ranging from modern and postmodern gallery art to rock and roll and hip-hop.

The centerpiece of the show is a custom-modified 1963 Chevy Impala—with hydraulic lifters of the sort that raise different portions of the car body a few feet off the chassis (in modern dance such movements would be called isolations) to make the car seem to kind of leap-frog down the street—and covered, wrapped, except for a few gold-plated accessories, most notably a rabbit hood ornament, in a thick blanket of brown felt. The piece is called Beuys N the Hood, with references to seminal postmodern German conceptual and performance artist Joseph Beuys and John Singleton’s classic ’hood-revelatory film of homonymous title, but slightly different misspelling, Boyz n the Hood.

Beuys served as a Luftwaffe crew member during World War II, when his plane was shot down over the Crimea. He survived the crash, but with multiple broken bones and other injuries, but was nursed back to wholeness and health, according to his account, by nomadic tribesman, whose treatment method was to wrap him in felt and fat. As for the rabbit hood ornament, one of Beuys’s famous performance pieces consisted of him gently cradling a dead rabbit in his arms, softly talking to the rabbit, explaining art to it. (Beuys is not an easy artist to get a handle on.)

A cluster of Beuys references also occur in a Reiman video included in the exhibit. Among many facets of his artistic persona, Beuys saw the role of the artist as a shaman, a medicine man, whose function was, through some sort of ritual—dance, song, imitative costume—to communicate with human ancestor spirits, particularly animal ancestors, totems. He was also an environmental artist, much concerned about civilization’s ravages on the natural environment. The Reiman video features an American Indian in an open prairie setting marred only by a distant enormous pillar topped by the McDonalds double arches logo, in a variety of costumes but ultimately a Washington Redskins football uniform complete with helmet, performing what looks like ritual dance and chant that evolves into what looks like stalking prey, now in a deer-hide disguise, with full deer head and antlers, over the Redskins uniform. And the occasional presence of an actual coyote, scurrying through the tall prairie grass, on the prowl for his next meal.

The coyote is a signature Beuys performance art accessory. In a performance piece in a New York City gallery called I like America and America likes me, he spent three days in a room with a wild coyote, wrapped in a felt blanket that the coyote would sniff around curiously—no doubt as mystified as any onlooker at the whole strange business—and ultimately tug at, and partially tear to shreds. But no harm done to man or beast, and after three days Beuys and the coyote got to be more or less friends. By the end of the performance, Beuys was able to give the coyote a hug.

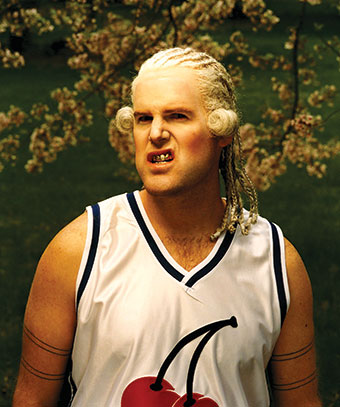

In a photographic series that combines the Boyz n the Hood theme and American history, Reiman presents a basketball team vaguely recollective of George Washington’s army—the team logo is a pair of cherries, from the story about the cherry tree and can’t tell a lie—in poses and actions reflecting more contemporary than historical times. Crossing the Delaware, for example, for a road game, occurs in the luxurious comfort of a stretch limo.

Further mixing high art and popular, on a table nearby are small models of a number of iconic pop culture sculptural objets d’art in the form of pro sports league championship trophies—the Stanley Cup, the Superbowl trophy, the NBA trophy—and iconic high art sculptures—Brancusi’s blocky Endless Column and Tony Smith’s Cigarette, the original of which stands outside the Albright-Knox 1962 building.

Several pictorial works or series involve play-on-words fusions of the names of high and popular artists. One called Michael Jackson Pollock shows a sort of Michael Jackson figure making sort of Jackson Pollock drip and splash paintings on a canvas on the floor of his barn studio. A video called David Lee Rothko, American Mudra overlays snatches of David Lee Roth stage performance gyrations against the staid background of the Mark Rothko art meditational chapel. There are a number of other references to David Lee Roth and Van Halen, that band, that brand of frenetic rock and roll, the soundtrack of Reiman’s coming of age, apparently.

Beuys had a similar interest in pop music and puns. He composed a pop song entitled Sonne statt Reagan. Ronald Reagan, that is, “Reagan” sounding like “Regen,” the German word for “rain,” so the whole phrase sounding like “sun instead of rain,” but the pun making it a political statement. Beuys was a socialist and pacifist as well as environmentalist, a whole set of social/political/economic positions the Republican Party, pretty much beginning with Reagan, has studied how to vilify.

The exhibit is entitled Can’t Stop Reiman. What? Another pun! It continues through June 29.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n22 (Week of Thursday, May 31) > Can't Stop Reiman This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue