Time Out of Time

by Woody Brown

Bruce Jackson and Diane Christian revisit their work on Death Row with In This Timeless Time

Bruce Jackson and Diane Christian are two of Buffalo’s most active scholars, writers, and filmmakers. Their curricula vitae might be called impressive, or more appropriately, mind-boggling. Jackson is the recipient of everything from a Guggenheim Fellowship (1971) to a Grammy nomination (1974). He served in the United States Marine Corps for three years before receiving his BA from Rutgers University (1960) and his MA from Indiana University’s School of Letters (1962). For four years (1963-1967) he was a Junior Fellow in Harvard’s Society of Fellows. He is the editor or author of 30 books, and, in collaboration with Christian, the director of five films. He is a prolific photographer whose work has been published and shown in too many places to name. Most recently, he was appointed the James Agee Professor of American Culture at SUNY Buffalo (2009), and just last week, the president of France appointed him chevalier in both the Legion of Honor and the National Order of Merit.

Christian received her PhD at Johns Hopkins, training in the History of Ideas tradition. Her studies emphasized the philosophical, religious, and cultural complexity of literature and art. She wrote on William Blake, a radical religious poet and painter whom she credits with wrestling her out of the convent. Her work in prisons began in college, teaching catechism in a Juvenile Criminal Facility. She also taught poetry in the Women’s Unit of the Arkansas State Prison. Her interest in violence, religion, and war is also reflected in her essays for Counterpunch, many of them collected in the book Blood Sacrifice (2004). Another collection titled The Priesthood of Death will be published by Counterpunch. She and Jackson currently conduct the Buffalo Film Seminars every Tuesday during the school year at 7pm at the Market Arcade. The seminars are open to the public and to date they have shown over 300 films.

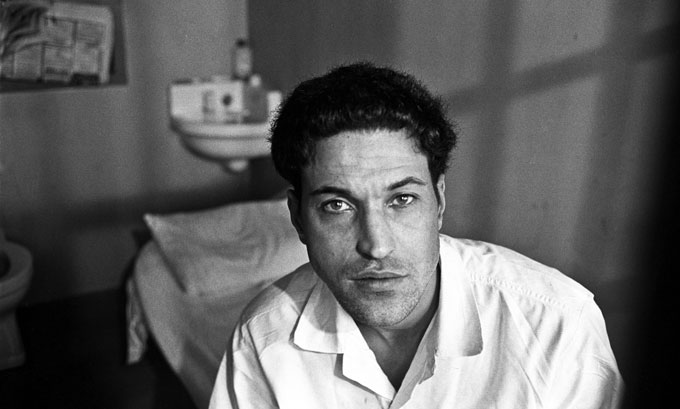

On April 16, 2012, the University of North Carolina Press and Duke’s Center for Documentary Studies published Jackson’s and Christian’s In This Timeless Time, a stunningly beautiful hardcover book of photographs and essays that follows up on the fates of the condemned men they met on cellblock J in Ellis Unit of the Texas Department of Corrections, Death Row. The book is separated into three sections: “Pictures,” “Words,” and “Working.” The first consists mostly of the gorgeous photographs Jackson took while Christian was interviewing the inmates. “Words” contains commentary written by the authors in 2011. This section is lucid and informative about everything from the individual inmates’ histories and experiences to the slothful circuitousness of the legal system as it deals with people on Death Row. Part 3, “Working,” describes the process of documenting Death Row and the unique challenges that accompanied their unprecedented, uncensored access. As Jackson mentioned during our conversation, “The work we did at Ellis Unit could never happen now. They just wouldn’t allow it.”

In 1979, Jackson and Christian travelled to Texas to make a documentary on a budget of about $25,000—“$65,000 short of the accepted production minimum,” Jackson said. The result is one of the most deeply moving projects on prison ever produced. Three works were assembled from their initial research: the documentary Death Row (1979), the accompanying book of the same name (Beacon Press, 1980), and finally In This Timeless Time, the beautiful and devastating final chapter. Each copy of In This Timeless Time comes with a DVD of the documentary film, a work of amazing power and grace that was instrumental in the abolition of the death penalty in France. It is largely because of Jackson’s work on prisons over the last 40 years that he was appointed to the Legion of Honor and the National Order of Merit, two distinctions that are rarely awarded to foreign nationals. Previous recipients include Hector Berlioz, Auguste Rodin, and Édouard Manet. I sat down with Jackson and Christian to discuss their lives, their work, and Death Row.

AV: I’d like to start off by asking you why you produced In This Timeless Time now.

Bruce Jackson: Diane and I did the work for Death Row in 1979.

Diane Christian: The film came out in December ’79 and the book in ’80.

Jackson: What we wanted to do with that pair of works was basically create a snapshot in time of that institution. And then as it kept going and going, and we found that there were still people like [economist Isaac] Ehrlich [who infamously claimed that each execution prevents eight new homicides, and whose arguments Justice Thurgood Marshall destroyed in his dissent in Gregg v. Georgia, and who is a professor at SUNY Buffalo], we decided we would take a look at what happened to those people we saw. Who is alive? Who is dead? We did [our initial work] during a very brief interregnum in the death penalty when the courts were redefining what it would take to kill. And we decided to take a look at what happened.

Christian: In the first book, we only had a two-page postscript that said our point of view. Now, we have a much more extensive analysis of our work and our point of view.

AV: The first event I associated upon reading this was the recent Republican presidential debate in which Brian Williams asked Rick Perry about his record of executions. Williams said, “Your state has executed 234 Death Row inmates, more than any other governor in modern times.” The crowd applauded here. He continued, “Have you struggled to sleep at night with the idea that any one of them might have been innocent?” Perry responded, “No, sir, I’ve never struggled with that at all.”

Christian: I think America is so blind about its violence. We think we’re the good guys, we think that we’re really not rapacious, and the truth is—just yesterday the [New York] Times did a piece describing how Obama has “Terror Tuesdays” in which he puts people on the kill list. Literally, this is a crime against humanity, according to an awful lot of people. And it’s certainly wicked to do it against your own citizens, and we have a blindness toward it.

Jackson: We’re the only Western industrialized country that has a death penalty.

AV: It seemed that over and over there were actual obstacles put in place by the State of Texas to considering any exculpatory evidence.

Both: Absolutely.

AV: So that’s their position, saying, “There was nothing in violation of the Constitution in the initial trial. There may be new exculpatory evidence, but we will not touch it as the Supreme Court because Troy Davis was convicted by a jury.” I have a quote from Scalia’s decision here In re Troy Anthony Davis on Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus: “This Court has never held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a habeas court that he is ‘actually’ innocent.”

Christian: And then it goes back to the state.

AV: Whereupon [Texas Governor] Rick Perry says, “I’m not considering that.”

Jackson: He says, “I don’t care.” And that’s what happened with [Cameron Todd] Willingham.

[Willingham was convicted of murdering his three children by arson in 1991. Despite significant doubts that Willingham committed the crime, as well as a trial that was complicated by recanted testimonies, a shady and inconclusive arson investigation, and the involvement of psychiatrist James Grigson, whose testimony for the prosecution in more than 160 capital cases earned him the nickname Dr. Death, Willingham was executed in 2004. Grigson testified that defendants posed a dangerous and enduring threat, which is one of the requirements in Texas for the death penalty. Grigson determined future dangerousness in Willingham’s case based on his “tattoos and fondness for heavy metal bands.” In June 2009, Texas ordered the case be reexamined, and the result was the Beyler Report, an investigation conducted by Dr. Craig Beyler, who was hired by the Texas Forensic Science Commission to review the case. The Beyler Report found that “a finding of arson could not be sustained,” and further that the testimony of Manuel Vasquez, a fire marshal at Willingham’s trial, which was essential to his conviction, was “hardly consistent with a scientific mind-set and [was] more characteristic of mystics or psychics.” Just as the Texas Forensic Science Commission was going to meet to discuss the report, however, Governor Perry, apropos of nothing, replaced the chair of the Commission and two other members. The new chair promptly cancelled the meeting.]

Jackson: In 2004, an arson expert named Gerald Hurst literally bought the house next door to Willingham’s and set a fire the way the way Vasquez thought the fire had started, except Hurst started the fire with an electrical malfunction. The blaze made exactly the same tracks—everything about this second fire looked the same as Willingham’s house had. So Hurst went to Governor Perry and presented the results of his experiment. Neither Perry nor the Board of Pardons and Paroles read the study or considered it. They just executed him.

AV: Why do you think that is?

Christian: They’re politicians, they’re running for office. They want to appear tough on crime. Even Clinton did this in the ’90’s when he was running for president. He went back to Arkansas and executed somebody. It’s politically venal, and that’s why the sheriffs and the attorneys general also do it.

Jackson: And it’s easy. Because you look at who these people are—they’re not people who live on Rumsey Road, they’re not children of lawyers. When we were there, there was one guy with retained counsel. He was a college athletics coach on Death Row for the insurance murder of his wife’s parents, and the only thing he would talk to us about was the weather. He was friendly, but he said nothing. And he got out. Because he had paid counsel. This does not mean that legal aid is always terrible, but it is better in some states than others, and it often does not compare to having retained counsel. They simply do not have much money to investigate cases, and this is why the Innocence Project has been so important. Independent of anyone, they’ll get interested in a case and they’ll go ask for DNA samples. And Texas fought against giving samples in old cases.

AV: I don’t understand that. Why?

Christian: Well, because they’re in the conviction and imprisonment business.

Jackson: But why a district attorney who is three people down the line from the DA who got the conviction in the first place would fight it…the same thing happened in New York City with the Central Park Jogger case.

[In 1989, Trisha Meili was jogging when she was brutally beaten and raped. Her skull was cracked so severely that her left eye was completely removed from its socket. Despite a fatal prognosis, she survived, though she still experiences physical and psychical aftershocks. A quick police investigation pinned the blame on gangs of black teenagers. The NYPD released the names of the suspects to the press despite normal police procedure that dictates that the names of juveniles should be withheld. Five suspects, or the Central Park Five as they were called, were brought to trial and convicted. Four of the five made taped confessions after hours of intimidation and coercion, and all of their testimonies implicated the one who did not. In 2002, Matias Reyes, a convicted rapist and murderer who was serving a life sentence, confessed to the crime. Subsequent DNA analysis confirmed his confession, and the convictions of the Central Park Five were vacated.]

Jackson: They had no physical evidence against any of these guys. They were just five black kids. This is a case tried by one prosecutor. New evidence comes forward, a man confesses, DNA tests are done that validate his confession. Then the current New York prosecutor fights it. It’s not just the South. It’s a prosecutorial frame of mind: “If they’re in our system, they’re guilty.” Foucault begins his book on prison talking about somebody being tortured. He says that the whole idea of torture is to get you to confess, and one of the reasons they have to get you to confess is if you weren’t at least partially guilty you wouldn’t be being tortured.

AV: It’s a tautology.

[One of the most striking inmates in Death Row is Thelette Brandon—sentence reduced to life, July 28, 1982; eligible for parole since August 2, 1984. At the time of filming, he had clearly lapsed into psychosis of some degree. He was always moving, dancing. “Every night, Brandon argued for hours with Emily and George, a couple that he insisted lived in the pipe chase,” Jackson and Christian write.The Texas Department of Criminal Justice offender registry currently lists his release date as 9999-99-99.]

AV: After finishing In This Timeless Time, I was thinking a lot about the incidence of mental illness, specifically with regard to Thelette Brandon.

Christian: Highest IQ on the Row.

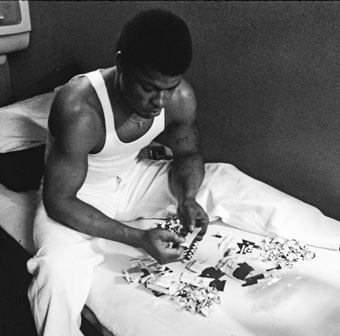

Jackson: One of the things about people on the Row is that they become compulsive. There are so few things over which they have control and there are so few things they can do. So the things they can control, a lot of people get extremely compulsive about them. Some people obsess over the arrangement of their towel on top of the one bookcase they have in the cell. You see in Death Row the way Kenny [Kenneth Davis, sentenced reduced to life, November 13, 1981] folds cigarette wrappers. The infinite patience he takes with them. He would spend all day making them into picture frames or crucifixes. Or [Thomas Andrew] Barefoot [executed, November 30, 1984] rolling his cigarettes every Wednesday. He wove this whole fabric around that day, saying that it was his Lord’s day, that it was prayer. Because there is so little.

Christian: And now it is so much worse.

AV: In footnote 32, you provide the URL for attorney Yolanda Torres’s recent photographs of the Polunsky Death Row.

Jackson: The single lightbulb, windowless except for the slit in the door, a small rectangle. For years, decades people live in that.

Christian: One of the things that the documentary unfortunately doesn’t show is that if you stood in the center of the cell and reached out your arms, you could touch both walls easily. And these men were big, most over six feet tall.

AV: Not to keep harping on this, but I feel like some degree of mental illness has to be a necessary event for all of them. The incarceration itself in cells like that seems to constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

Jackson: [Thelette] Brandon, I don’t know what he was like before he was on Death Row, but when I saw him on the Row, he was never not moving. He threw a coffee jar at the bars of Donnie’s cell [Murriel “Donnie” Crawford, sentence reduced to life, November 27, 1987; paroled April 2, 1991], and that’s what they would do sometimes in prison to blind someone because the glass would explode into thousands of pieces. I asked him, “Why did you do that to Donnie? He was your friend.” He says, “I don’t know, Bruce.” This isn’t five minutes later I’m talking to him. He says, “I don’t know, I wanted to do it to Wolf [Wilbur Collins, sentenced reduced to life, February 1, 1983].” “Why did you want to do it to Wolf?” “I don’t know.” Brandon’s was the only cell I didn’t go into. If he couldn’t remember why he tried to blind a friend of his, you know…

AV: And there was no reason for him to lie to you.

Jackson: Oh no, no. Donnie, when I asked him, said, “I don’t think even Thelette knows why he did what he did.”

AV: Thelette’s voice ends the film.

Christian: And it’s wonderful, beautiful. He talks about what’s going on Iran, and it’s still going on in Iran!

Jackson: Diane thought it was poetry, I thought it was totally crazy.

AV: Crazy poetry.

Jackson: It is, it’s both. Thelette was like a ping-pong ball, like Brownian motion of the mind.

Christian: He talks about the people of the world and the politics of the world. “Understanding the real language that is being spoken,” that’s the last line.

Jackson: The thing is, Death Row is a crazy place. It is a place where everybody goes around pretending they’re living a normal life, but they’re not living a normal life. They are waiting to find out if people they have never seen and never will see are going to decide to put them to death. And whether one day they will be taken to that other building 18 miles away and put in one of those little cells for about four or five hours and then put on a table and killed.

AV: The question then becomes: How do you maintain any semblance of a conscious life like that?

Jackson: There are two different kinds of prisons: There is the kind where you do time, and that’s what you’re doing, you do time; and then there are others where time is not allowed, it is a timeless time. Death Row is one of those, Guantanamo is one, Abu Ghraib is one. Those prisons where you are not charged, you cannot answer the question against you because no question is asked, or those prisons where the length of time and your behavior matter not an iota. And madhouses.

AV: I’m wondering about Kerry Max Cook. He was exonerated, and he wrote a book about it [Chasing Justice: My Story of Freeing Myself after Two Decades on Death Row for a Crime I Didn’t Commit (2007)], and he was in prison for 22 years. How did he keep from losing his mind?

Jackson: We asked Kerry that. We talk on the phone a lot. He said, “People often ask me, ‘How did you keep from losing your mind?’” And he said, “I always answer them, ‘I don’t know that I didn’t.’”

In This Timeless Time is available at Talking Leaves Books.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n25 (Week of Thursday, June 21) > Time Out of Time This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue