You Write "Theatre," I Write "Theater"

by Anthony Chase

The emotional question and history of a difference over spelling

Disputes over how to spell “theater” happen with surprising frequency in my world. The issue recently came up in a discussion of the signs in our city’s theater district. Typically, as the argument flares, the two sides promote their view with militant ardor, neither side offering any reasoned evidence to support its entrenched opinion, beyond personal comfort and preference. Sometimes people assert total fictions, arguing things like “One spelling refers to the art, the other to the building,” which is untrue.

The fact is that people are oddly attached to the way they spell that word, and there are reasons the discussion is so emotional. The history of the spelling is actually very instructive.

When Noah Webster published An American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828, his effort served to standardize American spellings for numerous words. This was not done arbitrarily. The push for spelling reform was a continuation of the fight for political independence from Great Britain and the advancement of American democracy.

As a spelling reformer and political activist, Webster argued that complex English spellings impeded literacy among working-class people, especially immigrants. He associated unencumbered social advancement with the idea that all men are created equal. His dictionary was part of the great American experiment.

Guided by this principle, Webster established distinctly American spellings consistent with phonetics, like “color” instead of “colour”; “center” instead of “centre”; “honor” instead of “honour”; “gray” instead of “grey”; “counselor” instead of “counsellor”; and so forth.

He also determined that the American spelling of “theatre” would be “theater.”

The newly democratic nation quickly and permanently adopted many of Webster’s standardized American spellings with remarkable unanimity. Some they rejected: “soop,” for example, did not replace “soup”; “ake” did not replace “ache”; “spunge” did not replace “sponge.” But American spellings for numerous words derived from French, Latin, and Greek that end in “-re” were enthusiastically adopted, including spellings for “centre,” “calibre,” “fibre,” “goitre,” “litre,” “lustre,” “manoeuvre,” “meagre,” “metre,” “mitre,” “sabre,” “saltpetre,” “sombre,” and “spectre.”

The story of “theater,” however, is unique.

The American theater at this time was still dominated by British actors and managers. In fact, the first great American-born classical actress, Charlotte Cushman, did not make her professional debut until 1835, seven years after the appearance of Webster’s dictionary. Her mentor, the British tragic actor William Charles Macready, urged her to refine her art in England.

Many of these British theater practitioners and their Anglophile protégés stubbornly maintained the British spelling of “theater,” even while adopting American spellings of other words. Of course, they had a vested interest in keeping the American public convinced of their artistic superiority, especially with competition from a new generation of American-born actors on the horizon.

In addition, conscious of the stigma associated with their profession at the time, some thought the British spelling sounded classier and more respectable, and so, like retail stores that call themselves “shoppes” in order to put on pretentious airs of “olde worlde” sophistication, many theaters sought to promote an air of genteel refinement by calling themselves “theatres.”

To this day, many American theaters use the spelling “theatre” in their names.

Nonetheless, despite these promotional ploys, the prevailing American spelling remains “theater.” In fact, lexicographers seem quite decided on the issue.

Garner’s Modern American Usage labels “theater” the American spelling, “theatre” the British. The Associated Press Stylebook similarly requires “theater,” unless the proper name of an institution departs from that spelling. The Chicago Manual of Style uses “theater.”

The New York Times, America’s foremost arbiter of theatrical judgment, uses “theater,” and even goes so far as to change the spelling of a theater’s proper name from “Theatre” to “Theater” if it is listed among other theaters.

The U.S. News and World Report Stylebook uses “theater,” as does the UPI Stylebook, the Washington Post stylebook, The Columbia Dictionary for Writers, and the National Geographic Style Manual.

If this is so, why does the issue persist at all, and more to the point, why do some people get so worked up over it? Indeed, those who prefer the British spelling can be persuasive to the point of coercion. Just look at the names of theaters around this town.

Again, history can shed light on the subject.

Interestingly, this lexical divide between “theater” and “theatre” is one of the last visible remnants of a class-coded Anglophilia/Anglophobia that permeated social life in the early years of our country. Often this reality produced profound sociopolitical consequences.

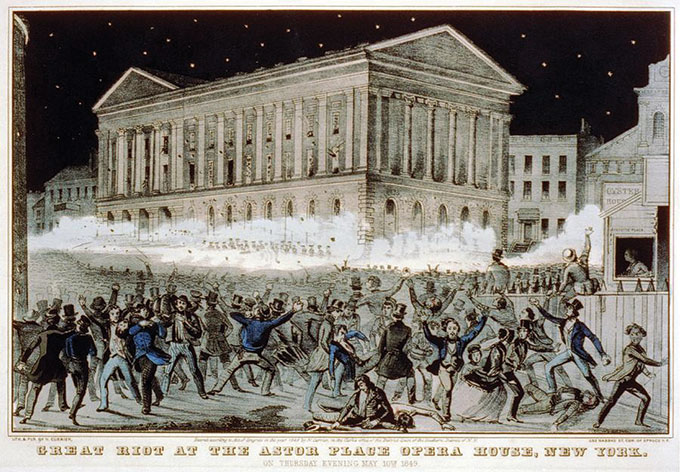

Consider the Astor Place Riot of 1849. This was the deadliest public disturbance in the United States up to that time. The riot pitted immigrants and other working-class people against powerful upper-class New Yorkers who deployed the city’s police and state militia to enforce order. It was the first time government authorities had ever fired live ammunition into a crowd of citizens in this country. As a direct consequence of this incident, the New York City police force, only four years old at the time and armed with wooden clubs, would become the first police force in the nation to be armed with deadly weapons.

The riot grew from a rivalry between actor Edwin Forrest, the first true star of the stage to be born in this country, and Macready (Cushman’s English mentor). The press enjoyed comparing the two, and Forrest encouraged this by touring to cities where Macready was appearing in order to perform in the same Shakespearean roles.

Fans of Macready and Forrest were largely divided along class lines, with the wealthy preferring the refined and aristocratic English actor and working people enthusiastic for the powerful and emotionally explosive American. Macready openly looked down on Americans, viewing them as vulgar, uncultured, and ignorant. Forrest was frustrated by English domination of the American theater.

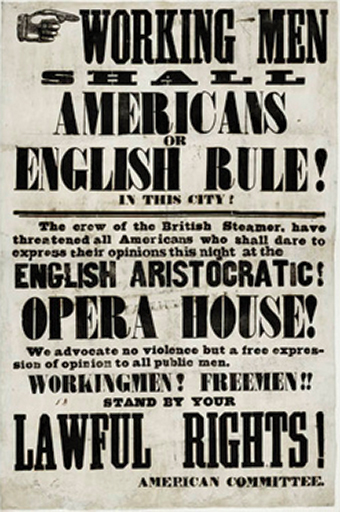

During this time, working-class Americans felt a growing sense of alienation from all things English, a sentiment that was aggravated by an opposite tendency in the upper class. While the nation had separated from Britain politically, and we had embraced the ideal of social equality on paper, in reality, we were still a nation divided. The wealthy continued to discourage the social advancement of immigrants, and slavery persisted. This was a time when a sign that read “NINA” in the window of a business would be understood by all Americans to mean “No Irish Need Apply.” Help-wanted advertisements that explicitly excluded the Irish can be found in the New York Times from 1851 until 1923.

Noah Webster disapproved of both slavery and obstacles to the advancement of immigrants.

On the street, “nativist” working-class Americans and Irish immigrants may have battled each other in gang warfare, but they were united in their patriotic fervor and hatred for all things English, which they associated with discrimination against them by the upper class. This conflict reached a fever pitch in May of 1849 when Macready and Forrest were both scheduled to appear as Macbeth in New York City on the same night: the Englishman at the Astor Place Opera House, and the American just blocks away at the Broadway Theatre.

The two actors had unwittingly become symbols in a class struggle and a fight over the future of American culture.

Macready’s opening on May 7 turned disastrous when Forrest fans jeered and threw trash onto the stage from their balcony seats. Three days later, on the night of May 10, when thousands of working-class Forrest fans converged on Astor Place, intending to disrupt Macready’s performance again, the authorities were ready. At first they shot into the air, but when the unruly throng refused to disperse, the state militia fired directly into the crowd at close range. In an instant, 22 people were killed and more than 120 injured. Almost all of the casualties were from the working class. Seven of the dead were Irish immigrants. One was a child.

There was a huge public outcry against the unnecessary and excessive use of violence, but the city’s elite were unanimous in endorsing the severe handling of the rioters. As James Watson Webb, publisher of the New York Courier and Enquirer, wrote:

“The promptness of the authorities in calling out the armed forces and the unwavering steadiness with which the citizens obeyed the order to fire on the assembled mob, was an excellent advertisement to the Capitalists of the old world, that they might send their property to New York and rely upon the certainty that it would be safe from the clutches of red republicanism, or chartists, or communionists of any description.”

Webb had previously used his newspaper to spread false rumors that abolitionists encouraged miscegenation among their daughters, fueling the New York anti-abolitionist riots of 1834.

The Astor Place Riot is a watershed moment in the history of American culture. The emotion that escalated into that conflict is still discernable in strong opinions about the spelling of the word “theater.” This was an event that furthered a process of class alienation and segregation. Symptomatic of this was a division of American entertainment into categories of “respectable” and “disreputable” that is parallel to attitudes toward the use of “theatre” and “theater” still today.

The militant preference for the British spelling among some theater practitioners in this country actually originates with this elitist impulse. “Disreputable” was code for immigrant or working class. Professional actors gravitated to “respectable,” “legitimate” “theatres.” This is the same impulse that made the impresarios of vaudeville feel justified in imposing racial segregation at their theaters. This is the same elitist impulse that inspired the community leaders of past eras to establish clubs that were “exclusive.”

While the design and very location of the Astor Place Opera House were intentionally chosen to draw a strict dividing line between social classes, now the owners of theaters and other public accommodations found new ways to make specific classes of people understand that they were not welcome. The decision to use the un-phonetic British spelling of “theater” is a subtle example, intended to send a message that connotes cultural superiority, refinement, and exclusivity.

Ours is a class-conscious and colorfully storied city. The history of class struggle here is contained in our community institutions, the design of our roads, and in the segregation of our neighborhoods. We see it in the litany of buildings that have survived and those that have been torn down. Every time I see another theater open and call itself a “theatre,” I recognize a surviving remnant of an impulse that is truly regressive, and I think to myself, “Elitist Mr. Webb has just scored a quiet little victory over egalitarian Mr. Webster.”

I understand that for some people, the preference for the British spelling of theater represents little more than comfort with the spelling they know, or a belief that “theatre” looks ever so much nicer on the marquee and in the “programme” and will better attract audiences. They’re trying to send the message that their theater is so good it’s practically European!

Apart from the implicit assumption that American means inferior, I suppose that’s harmless enough. But the ways in which that spelling invisibly insinuated itself into the American consciousness are not harmless. The impulse to use that lone “-re” spelling and no other in the language is an artifact of a history of elitism, exclusion, and oppression.

You can call your theater a “theatre,” and you can call your store a “shoppe,” if you think it will attract customers. You can even build a gated community, call it “Pointe Buffalo,” and exclude anyone who’s not a “membre” from dining in the “bar & grille” at the “centre,” if that’s the way you want to live. But public signs really should use the widely accepted, well considered, and hard-earned American spelling, “theater.” Sometimes, spelling does count.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n6 (Week of Thursday, February 7) > You Write "Theatre," I Write "Theater" This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue