From Haiku to the Blues

by John Kryder

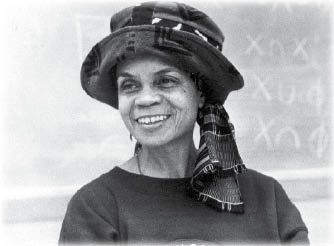

Next Thursday, April 26, Sonia Sanchez headlines the fourth annual Buffalo/Williamsville Poetry, Music, Dance Celebration at Kleinhans Music Hall (7pm, free). Sanchez, whose work addresses the African-American experience from slavery to modern forms of opporessions, is a recipient of the Robert Frost medal in poetry and the Langston Hughes Poetry Award; she has been nomiated for the National Book Critics Circle and the NAACP Image Awards. Recently she spoke with Artvoice about her work:

Artvoice: From the renga, the ancient Japanese collaborative form, came the haiku, which appears often in your books. What led to your interest in haiku?

Sonia Sanchez: I was at the H Street bookstore, looking at some of the anthologies; up on high was this thing that said Japanese Haiku…at 19 1⁄2 years old, I opened this book and started to read this haiku…and slid down on the floor and started to cry because I had found me, secreted in between these three lines I had found me, my soul, my spirit.

I’m doing a long essay, “From Haiku to the Blues,” because I began to talk about the connection between the two. People say, “Ah, the haiku, you capture this great image, like the sun is setting or the sun is coming up,” but the thing about the haiku is always the other side of that brightness. There’s darkness there. When the sun sets you have also what happens in the night, what happens on the other side of the haiku. I think Rilke says, “After beauty comes terror.” And the same thing happens with the blues.

I want to let people see the connection between that form and the people who invented it. I think that form has a lot to do with staying alive. When the Japanese were incarcerated in concentration camps, in order to survive they wrote the haiku. The whole idea of beauty and horror at the same time occurs in the haiku…the haiku is a discipline about living.

In the ’80s, when I was burnt out and very tired and really working too hard and taking care of a lot of family members at that time, I wrote the haiku. I could not go beyond the three lines…when I went back and looked at that notebook I understood that it kept me alive. When you listen to a blues singer sing the blues, there is that one long breath with the first stanza…when you know it works you’ve said the haiku in one breath and when you do the one breath you know you’ll take another breath and know you’re alive. There’s always with the haiku something that’s come before and something that’s coming afterwards, which is probably part of that subconscious conversation that comes within the haiku, and the same with the blues.

AV: Our Celebration features the connections between poetry and music. How do you see the relationship between poetry and music?

SS: All poetry has music in it. The thing that Louise Bogan used to tell us is that we had to learn to read our poetry. Reading it out loud took it off the paper…You can give that poem life by this breath that you have. Now the music part of my poetry is that I always heard music when I wrote something…I would put in the margins “to be sung” and left it alone.

I was doing a reading at Brown, and this young African-American man raised his hand and said, “Professor Sanchez, I read your Coltrane poem, will you read it.” And I said, “I’ve never read that poem out loud.” And in that poem I used my voice, I stamped my feet, I hit my hat, I did everything you can possibly think with this poem. It’s a long, long poem…and as I read that poem I recognized the voice that I had to use with my poetry from then on. And I came off that stage and hugged him and I said, “Thank you for making me read that because you made me realize I had not been using my voice in the way I should be.” He released me. From then on I began to experiment and make use of the sound that the voice could make, assuming instruments…I moved beyond just saying a word.

Plus I came from a household of musicians. My dad was a musician so we heard music in my house. I heard at night the blues and Billie Holliday and Dinah Washington. I heard Duke Ellington, the big-time jazz, Erskine Hawkins, Coleman, all these people. But also I had begun to listen to, some years later, the bebop. At some point, it wasn’t by chance, someone said, “Let’s do some poetry with jazz.” You say, “Yeah, I can do that.”

AV: How has your development as a poet grown out of the roots of your childhood?

SS: I started to write after my grandmother died. I used to imitate my grandmother, this Southern voice she had, this English she spoke, which was not an educated English…and she let me do that. So, from a very young age, my ear heard the musicality of her speech, of what I call black English. The aunts living in the house thought I was mocking her, and they would say, “Stop mocking Mama,” and she would say, “Shhh. No, let her be.” She had enough sense to know my tongue was enjoying that. I wanted to say it over and over again so I kept it with me. And one of the first poems I wrote was about that, about my grandmother and how she spoke. So when she died—I was six—I started writing about her, writing poetry, and continued writing poems. I wrote, and I wrote in high school, but because I stuttered I didn’t ever read them aloud to anyone at all.

AV: Our Celebration features six compositions based on your poetry. Eric Mahl, whose orchestral composition is based upon three of your haiku, noticed in your poems recurrences of water imagery and references to morning. Can you comment on these recurrences?

SS: We’re made up of water, which means also that our bodies respond to sound and speech…but I also think water is a feminine image, water is feminine is water is women. Morning, also—I try to subvert the image, how they say that the sun is a male image and the moon is a female image, and the moon comes out usually at night. I used to say around a lot of male poets, “The moon out when the sun out,” I’d say, “Go on!”—to subvert that image always. I also have made light a female image because I’d say, “Who’s up in the morning?” Quite often, women—before children, before husbands, before everybody. So to be this thing of light, this sun, is very, very female…just as I think poetry is light is sun is life, then I try to use these images that really do give us life.

AV: Chris Johnson-Roberson, whose orchestral piece will be danced, says your poetry not only resonates with readers on a personal and political level, but it excites with its fresh use of language and form. How have you struck a balance between these elements? Has this changed with age and experience?

SS: Many people who encountered the black poets in this country in the ’60s heard an angry group of people and we were angry for a reason, because we had not been told our history and herstory…we came out like, “Whoa, you really did enslave us.” We indicted everybody…it was not only the country but our own parents, preachers, you name the people. If you weren’t telling the truth, if you were part of the conspiracy of silence, then we indicted you. You had to say that and do that and let people understand that was really happening because most people were asleep in this country.

People forget that part of our emergence as poets and being heard in the ’60s was during a war too, so there was this amazing movement of trying to say to people, “This is what happened to people of color, to black people, to Japanese”—because when I went searching for myself I found Japanese in concentration camps…because we were excavating our own lives and history we found all these other histories and herstories.

AV: Our Celebration coincides with the re-publication of Homegirls and Handgrenades, first published in 1984. What is the significance of the re-publication?

SS: I’m very grateful to White Pine Press, a press that I’ve always looked at with a lot of admiration because it is a fine alternative press and one that should be supported constantly, as all the small presses should be protected and supported. I’m very grateful because it is a pivotal book of mine that talks a great deal about what has been going on in the country and in the world.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n16: Best of Buffalo (4/19/07) > From Haiku to the Blues This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue