Our Song & the Waterhouse Bar

by Anthony Chase

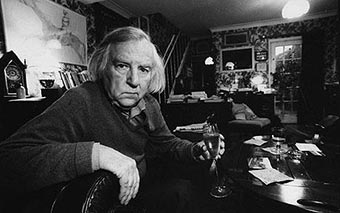

The New Phoenix's Robert Waterhouse pays tribute to his late father

Our Song, which opens next Friday at the New Phoenix Theatre, is a sentimental theatrical journey for its director, Robert Waterhouse. His father, Keith Waterhouse, the celebrated British novelist, screenwriter, playwright, and newspaper columnist, who died in September 2009 at the age of 80, wrote the 1992 play with Willis Hall, based on his own novel. On the night of the opening, the New Phoenix will dedicate the Keith Waterhouse bar, in honor of the playwright, in the lobby. Dignitaries from both sides of the Atlantic have contributed to the cost of the bar, including Dame Judi Dench.

“Yes,” confirms Waterhouse. “Dame Judi sent a check.”

While the elder Waterhouse’s career was centered in London, where his colleagues dubbed him “the King of Fleet Street,” the Keith Waterhouse bar is a recreation of a Manhattan bar.

“My father loved New York City,” says Robert. “He loved Grand Central Station and he thought New York was the height of civilization. He used to go to the Blue Bar—the old bar that they tore down at the Algonquin Hotel [famed home of the Round Table]. He loved it. He would sit there and talk to Hamlet, the Algonquin Hotel cat. Well, one day I got this thought, looking at the alcove under the stairs at the New Phoenix, ‘That’s my father’s American bar!’ And that’s how the idea got started. The bar itself is being built in [set designer] David King’s workshop, and I am sure that it will arrive at the last possible moment, and that it will be wonderful!”

While Robert often has to explain who his father was to Americans, in England he was a major celebrity, having catapulted to fame with his 1959 novel, Billy Liar, based on his own experiences working for a funeral director. The title character, a young Englishman who lives an uncommonly rich fantasy life, is often called “a British Walter Mitty,” though that description underestimates the enormous influence and seminal status of Billy Liar to British culture. The story captured the public imagination in Britain as a novel, as a 1960 stage play starring Albert Finney, and especially as a 1963 film version, directed by John Schlesinger, starring Tom Courtenay and a young Julie Christie. There was even a musical version, 1974’s Billy.

The elder Waterhouse also wrote the stage version of Billy Liar (with his frequent collaborator, Willis Hall), as well as the books for the musicals The Card, starring Jim Dale and Millicent Martin, and Budge, and many other stage works. For the screen, he wrote Whistle Down the Wind and A Kind of Loving, and he and Hall also did extensive, uncredited rewrites for Alfred Hitchcock’s film, Torn Curtain. In 2004, he was voted Britain’s most admired contemporary columnist by the British Journalism Review. In 1991, he was appointed to the Order of the British Empire.

His greatest success for the theater was Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell, a play inspired by his alcoholic colleague, newspaper columnist Jeffrey Bernard. The title was borrowed from the notice that The New Statesman newspaper ran on the frequent occasions when Bernard was too drunk or too hung over to write his column. In the play, Bernard, originally played by Peter O’Toole, finds himself locked in a pub after closing, and uses the circumstance as an opportunity to regale the audience with his wit and insight. A triumph, both for Waterhouse and O’Toole, Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell won the Evening Standard Award as Comedy of the Year in 1990. Buffalo’s David Lamb won an Artie Award for his performance of the role at the Kavinoky in 1994, and Robert Waterhouse was nominated for his direction. Keith Waterhouse traveled here to see the production—his only visit to Buffalo. He was lavish in his praise and charmed everyone he met.

The set for the original London production of Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell was a recreation of the Coach and Horses pub in the Soho area of London, which held a minute’s silence in memory of Waterhouse when he died, thereby sowing the seed in Robert Waterhouse’s mind for a bar memorial to his father in Buffalo. “This will be a recreation of my dad’s favorite American bar,” Robert says.

The play opening at the New Phoenix, Our Song, has never been seen in America before.

“Our Song,” explains Robert Waterhouse, “is about a married man who falls disastrously in love with a younger woman. It’s a study in folly. He knows it will end badly, but even as he sees himself falling madly into this affair, he can’t help himself. Roger Piper, the main character, is surrounded by people who are watching with concern. As he begins his descent toward disaster, everyone who cares about him tries to warn him.”

In the New Phoenix production of Our Song, Richard Lambert will play Roger Piper and Kelly Meg Brennan will play his young love. Christian Brandjes, Jeffrey Coyle, Guy De Federicis, Pamela Rose Mangus, and Bethany Sparacio will play the other characters in Piper’s life.

“It is a memory play,” Waterhouse says. “Piper is remembering an affair that caused him to lose his job, and almost his marriage and his sanity, as he is trying to exorcise it.”

Reviews for the novel were characteristically enthusiastic. “You stay gripped from the opening paragraph,” wrote London’s Daily Mail. “Waterhouse offers us the unsparing image of Everyman and Everywoman in the humiliating throes of irrational passion. Our Song crackles with insight about the nature of sexual obsession.”

“There is no denying the virtuoso skill with which Keith Waterhouse plays out the whole saga…by turns caustic, cryptic, funny and fatuous. It is a splendid read,” said the Sunday Telegraph.

In its main character’s recreation of the affair in his imagination, Our Song holds echoes of Billy Liar and Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell.

“There are lots of people who live in their own heads in my father’s work,” says Robert Waterhouse. “This came from his own personality, and a desire to keep creating characters who created witty realities through a vivid use of language.”

Robert Waterhouse explains that his father, himself, balanced two worlds—one that lived in language and another that was personal.

“When it came to his personal life,” says Waterhouse, “my father was very silent. He came from Leeds in the north. That is very silent stock. At the same time, he could be ebullient and expressive when he entered the realm of fiction as a raconteur. ‘Creating’ was personally liberating for him, and he would become larger than life and sparkling in the persona of storyteller, but when it came to private matters, he locked a door. The only way to get close to him was through language and work. Even our relationship as father and son was like that. Americans are always saying ‘I love you!’ We were very close, but we expressed it through talk about work and things like that. It was the kind of thing that is understood between you, and it was enough—because we are English, I suppose.”

Keith Waterhouse’s passion for language culminated in his writing of an extended stylebook for the Daily Mirror in 1979, called Waterhouse on Newspaper Style. Actually a series of witty essays on grammar and usage, organized in an A-Z format, the book is regarded as a classic textbook for modern journalism. He also wrote a pocket book on English usage intended for a wider audience called English Our English (And How to Sing It). He also founded the “Association for the Abolition of the Aberrant Apostrophe.”

While these descriptions might make both Waterhouses sound emotionally aloof, Robert reveals that his father was also tremendously sentimental. For instance, during his two-day visit to Buffalo to see his son’s production of Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell, Robert Waterhouse recalls his father becoming overcome with emotion.

“It was a very memorable visit with many funny incidents. I remember that our stage manager, Fred Wienberg, wanted to create this effect of the smoldering couch—and managed to set it on fire while my father was here. And I especially remember going to Garvey’s [restaurant on Pearl Street] after the performance, and when we got there with all the actors, my father got weepy. That was a big deal. He was very moved. He really loved and admired actors, and being in Buffalo to see his play, directed by me, was very emotional for him.”

I’m proud to say that I was a witness to that particular Waterhouse story. I clearly remember Keith Waterhouse’s friendly graciousness toward everyone he met, and his obvious love for his son, and yes, even seeing him become teary-eyed. He seemed to take great pleasure and pride in being called “Bob Waterhouse’s father.”

One can detect aspects of Keith in Robert Waterhouse. When Robert goes to England, he is the son of a celebrity. “It can be very flash bulby and grand and pretentious, and honestly, I do feel more comfortable here,” he says. Being in Buffalo, surrounded by good friends, suits Bob Waterhouse just fine.

Robert’s sister, Sarah, will come to Buffalo to see Our Song, which opens the day after Thanksgiving and runs through December 18 at the New Phoenix Theatre on the Park (95 Johnson Park). Call 853-1334 for ticket information of visit newphnxtheatre@aol.com.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n46 (Week of Thursday, November 18) > Our Song & the Waterhouse Bar This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue