Next story: Photographs by John Pfahl at Nina Freudenheim Gallery

Installations by Chantal Rousseau and Kyle Butler at Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center

by Patricia Pendleton & J. Tim Raymond

Mortal Lives

Two adjoining exhibitions behave as mantras, repetitious utterances in visual forms. Chantal Rousseau visits from across the border in Kingston, Ontario, with her installation, Harbingers of Doom, next to Mortality Tantrums, by Buffalo artist Kyle Butler. Rousseau’s animations deal with human frailty in the face of sex (desire) and death, while Butler involves himself with built and social environments. Both artists have proven abilities in drafting and painting. Expanding upon traditional methods, they each create artwork that moves beyond the paper or canvas to unexpected places. After leaving the exhibition and artist talks, we began deconstructing our observations that led to a joint effort for this week’s review: JTR looks at Tantrums and PP looks at Harbingers.

Kyle Butler is ambitious. An artist is a seeker of significance, using the senses to manifest a separate awareness from ordinary reality. The choice of working materials is finite, visible, and—once composed, arranged, or assembled—may even be saleable. Butler shows considerable dexterity in his approach to satisfying the visual, physical, and psychological categories in contemporary art presentation—the built environment, appropriated components, video, and handmade renderings that he refers to as “structured work.” He manages to keep all of these elements working together in a kind of post-industrial requiem. Chain-link fence sections, set into a platform, hold portions of a tree limb suspended in the grip of an anodized grid, resembling an insect caught in a spider’s web. The long, gnarled, twisted bark is pierced by the ruining matrix. The artist has invested in a view of reclaimed relics of property—both land and dwelling—at the interface of human habitation and the structured arrangements of modern civilization. He plays at the edges of coherence between intention and misdirection to create an atmosphere of marginality where his underlying pristine strategies of execution are meant to appear both accidental and random.

Butler’s wood platforms for the sculptural pieces offer an assembly of building materials worked out an industrial aesthetic that never strays far from art/refuse parameters. His sense of placement is askew, off-balance, tilted, an incompleteness that makes for conceptual leeway in interpretation. Minimalist armature accentuates the inner connection of raw materiality. The judicious placement of the work further gives the art room to breathe.

An abiding aspect of Butler’s work is the absence of form that creates negative space in his drawings, the links in the fence chain, and the spaciousness of the slanting porch. The ceiling lamp acts as a hopeful beacon shining upon each element of the installation to emphasize the margins of the void. The viewers are left to draw their own existential blueprints. A look at the video sojourn, Leisurely confronting the abyss, shows Butler harnessed as a beast of burden in the service of furniture, through the unpeopled streets of downtown. He ends up on the rocks at the waterfront raging out to the lake against the machinations of society in a cha somewhat too big for him.

Chantal Rousseau’s side of the gallery echoes Butler’s void in an installation of animated screens. The animated gif file commonly used in advertising has become a popular tool for artistic expression. Just last month, Tate Museum hosted a one-day exhibition of such works from artists using images from the collection. Transforming a still image with slight looping movement adds a mesmerizing quality, not unlike the simple “wiggle pictures” from long ago. We want to look over and over again, but why? It is not equivalent to looking at a painting that promises more. The cartoonish movement of these screens lends a feeling of slapstick that is suggestive of humor or play, even when the content is dark. While her material is fished from the sea of popular online imagery, she also borrows from the landscape and wildlife iconography of her country. The image is stripped from the found environment and hand-rendered before it is floated in the void of a screen.

The largest piece shows a park setting with a lake and two figures canoeing on placid water—until the animation makes them disappear. This tribute to the Canadian mystery legend of Tom Thomson, who went missing back in 1917, has become folklore after the sensational story popularized the artist’s landscape paintings. Rousseau calls this In the spirit of all artists who have disappeared mysteriously while canoeing in Algonquin Park: FAIL. What about all the artists who fail? Let us not forget those who mysteriously give up on art to work for the gas company or other life detours.

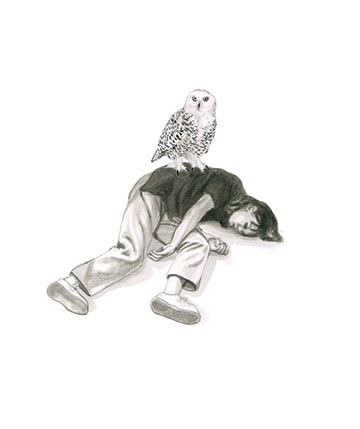

Rousseau references the memes (cultural symbols) that transport ideas rapidly from one individual to another online through viral transmission. The exhibition brochure cover shows Memento Mori. The graphic skull extends a long red tongue that wraps around another skull. Remember…you will die. Reminiscent of the Oroboros snake who is shown devouring its own tail and the serpentine red tongues found on the heroic paper figures of the late Nancy Spero. Rousseau’s women squeeze fish and move suggestively. The bikini-clad blonde will mean little if you have not heard of Kate Upton or observed the Cat Daddy dance, but familiarity with popular culture is central to relating to this work. It seems necessary also to refer to it as I comment on the work. The naked woman in Bird Love tugs on a constricting harness belt and gestures to shake loose a Falcon that has landed on her shoulder. Remember the outreaching hands of Tippi Hedren as she encounters Hitchcock’s swarm of birds? Predatory creatures and women—a common theme. A snowy owl hops up and down on top of a corpse in a piece titled And now let us weep for the lovely lovely ladies of CSI, another cultural reference that will mean more if you are familiar with the show that opens with the Pete Townshend song, “Who Are You?” and solves the mystery of a different dead body each episode.

Rousseau also paints. Her website displays a series of finches—appealing representational work. She is a member of the Kingston, Ontario artist group, Agitated Plover Salon. They install exhibitions in non-traditional venues, such as storefronts. By the way, a plover is a wading bird of Canada. Bird images have turned up in art since cave paintings, but they are especially prevalent in post-Twitter times. Anyone who viewed early episodes of the series, Portlandia, will recall “Put a bird on it,” the slogan in the parody about the bird design trend. My longer look into Rousseau’s work uncovered interest and layers of connection that a casual walk through the installation may not reveal. The screen surfaces are naturally impenetrable. Omens and signs blink a glowy mantra, but there is a coolness to this chant. Desire and death hang in a gauzy void. Perhaps one cancels out the other?

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n13 (Week of Thursday, March 27) > Art Scene > Installations by Chantal Rousseau and Kyle Butler at Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue