Next story: Pictures at an Exhibition: Revealed

Song of the Living

by Jack Foran

Charles Burchfield retrospective stops at the museum bearing his name

Everything shimmers in the work of artist Charles Burchfield. Everything vibrates. Everything pulses with life forces.

And for dramatic interest, there’s the ongoing struggle between the positive forces of light and color and music, and equally vital but shadowy monsters of elemental forces that can run riot in the artistic imagination.

A retrospective exhibit of the work of this superlative Buffalo artist opened last weekend at the Burchfield-Penney Art Center. In 1921, Burchfield moved here from Ohio to work for the Birge Wallpaper Company, and set up his personal artistic studio in Gardenville. But for inspiration he went to the fields and woods.

“I have been conscious of cicadas,” Burchfield wrote in a letter. A main object of his art was the representation of the music of nature—cicadas and katydids, notably, but also the more subtle music of grasses or trees—in painting. Or whatever once may have been grasses or trees. Fence posts and telephone poles, for example. Houses. Whatever was alive remains alive.

Visible wave forms representative of the vibrational essential character of sound come to represent the less raucous vital forces of all nature and former nature.

“I had been struggling in a painting to visualize the cry of a nuthatch, and then have the cry resound through the autumnal woods,” Burchfield says in a comment on Autumnal Fantasy, featuring pulsation signals emanating from eye-like and ear-like locations on trees.

Roughly similar means to similar ends in the Song of the Katydids. Though he notes that “actually, the ‘Song of the Katydids’ embodied the song of the cicadas as well as other insects (especially the tree locusts or short-horned grasshoppers).”

A good example of his application of wave forms to specifically visual and not aural subject matter is in The City, showing endless waves of urban landscape, like ocean waves, or successive mountain ridges.

But the vital forces can also be forces of menace, as in The East Wind, a threatening semi-abstract vision. Commenting on this piece, Burchfield says, “the east wind brings rain—to the child in his bed, the wind is a fabulous monster and the days of rain on the roof are frightful.” Similarly, about The Nightwind, he says, “to the child…the roar of the wind…fills his mind full of visions of strange phantoms and monsters…”

Even field grasses can be threatening, as in Wheatfield, in the almost terrifying depiction of grain stalks at the apex of their season of life, standing tall, but on the cusp of ripening.

And dark and foreboding caves figure centrally in a number of rather melancholy paintings, such as the early White Violets and Abandoned Coal Mine, and late Studies in Solitude.

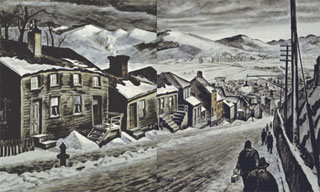

But the positive forces prevail, or are not discomfited. End of the Day depicts workers’ housing and a few workers straggling homeward, uphill, in the semi-darkness of a winter early evening. A bleak scene, but the very houses have a somber vitality “as though they had grown out of the earth or been part of it for centuries and would exist like that for untold ages to come, a symbol of the indestructibility of man and his defiance of time,” as Burchfield described the painting.

There are even epiphanies, visions of light. Apropos of a painting called Blue Dome of June, he wrote, “Today…I suddenly saw the cobalt sky behind and above the clouds develop (in my inner eye) into a beautiful blue dome, with a huge cloud above it, from behind which golden yellow light poured down on the earth below.”

Sometimes the visionary experience is in a blinding flash of light that obscures—blanks out—the whole central portion of the painting. As in Midsummer in the Woods. Or Winter Sunburst, where the subject scene is partially blanked out.

These almost classical visionary experience works are from late in the artist’s career and life, about 1960. He was born in 1893 and died in 1967.

The exhibit includes copious notebooks and notes—Burchfield was an inveterate notemaker to himself—and doodles and sketches. Part of the idea with the notemaking was that he was always going back to earlier work and concepts, trying to see how he could expand on these. Literally. There are examples of his taking an earlier work—practically all the works are watercolors on paper—and pasting paper strips along the edges, then extending the original subject matter into the new area.

A note to himself displayed above one of the expansion or extension examples says: “Before starting work go all thru all the former material…”

There is also a wallpaper room, wallpapered in a design he created for the Birge company, along with the original watercolor he made as a first step in the process. The wallpapered walls are then hung with Burchfield paintings, including several other originals of his wallpaper designs.

And a wallpaper corridor that illustrates the fascinating process of wallpaper making, from original painting to finished product.

This excellent exhibit, entitled Heat Waves in a Swamp, was curated by sculptor Robert Gober and organized by the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, in collaboration with the Burchfield-Penney Art Center. It was previously shown at the Hammer Museum, will be at the Burchfield-Penney until May 23, and then will go to the Whitney Museum in New York City.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n10 (The Drinking Issue: Thursday, March 11) > Song of the Living This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue