Next story: The Obsolete Man

Lives Lost

by Matthew Quinn & Geoff Kelly

Ben Perrone talks about his installation at the Burchfield-Penney, which mourns American lives lost in senseless wars

You’d think that every American artist would eventually adopt war as his subject. Conflict is the constant in the American experience, and sooner or later an artist’s work must engage the realities of his time.

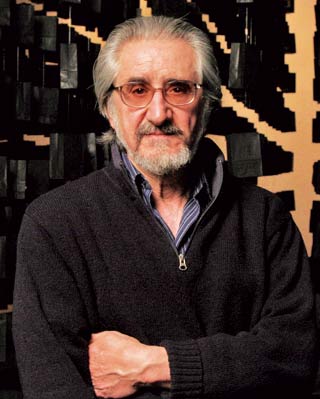

Ben Perrone, whose history as an artist in this community spans 50 years, taking in the great antiwar movements of the 1960s and 1970s, has just now taken up the subject of war in earnest. The result is a chilling installation at the Burchfield-Penney Arts Center titled War Ongoing Project, which opens this Friday, April 8.

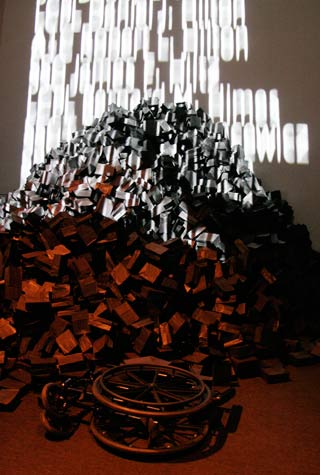

The centerpiece of the installation comprises 5,000 black paper bags that hang from the ceiling, more or less in rows, forming a wall that fills perhaps a third of the gallery—it’s about 15 feet deep and at least that high, stretching from wall to wall and floor to ceiling. Inside each bag is the name of an American soldier killed in the Vietnam war.

To enter the exhibit, visitors must push through the wall of hanging black bags, emerging into an open space. (“Voluntarily or involuntarily, they will be touching these bags that contain the names of casualties,” Perrone explains. “It brings them immediately into contact with the truth about what is going on with war. War is about people being killed.”) Another 5,000 bags, also containing the names of soldiers killed in Vietnam, are piled against the far wall; in front of the pile of bags are two wheelchairs. A projector scrolls a roster of the Vietnam dead on the wall above the pile. On the other two walls, a video montage created by Jeffrey Proctor loops images of ghostly figures and photographs of wounded Civil War soldiers.

The whole is accompanied by a composition for cello by Hugh Levick, interspersed with interviews with war veterans. The bags turn and quake gently in currents of air, catching stray light and color from the projections on three walls. One is acutely aware of the names contained in each bag. The effect provokes chills.

“I want to get people to understand that each on of these bags they see, that’s a life,” Perrone says. “That’s someone’s wasted life. A life that could have been lived. It’s waste not only that they weren’t able to live that life but that they weren’t able to live that life in a productive way. They weren’t able to do something for society, they weren’t able to propagate, to have children, to add to our wealth.”

Born in Pennsylvania, Perrone moved with his family to Buffalo in 1941. He was a poor student in high school who managed nonetheless to gain admission to UB, where he studied for three years before dropping out—an experience that confirmed for him that academics were not his strength. He joined the US Army, serving for two uneventful years as a clerk/typist in the brief lull between the Korean and Vietnam engagements. He returned to Buffalo in 1960 an enrolled in the Albright Art School.

“As soon as I got into art school, I knew I’d found a home,” Perrone says. “It was an exciting time. It was the time of the Abstract Expressionists. It was a time of turmoil in the country.”

At the Albright Art School, Perrone studied with Lawrence Calcagno, whose series The Black Paintings had made him a prominent talent in the Abstract Expressionist movement. According to perrone, Calcagno was not interested in teaching his students techniques; rather, he taught his students to explore media, to discover techniques and imagery rather than preconceiving them. Abstract Expressionism proved to be Perrone’s trope.

“The color, the freedom of it…it was very appealing to me,” he says.

During that time, Perrone fell into the company of artists like Wes Olmsted, Don Lazeski, and Harry Albrecht. He was hired as an assistant by the painter Adele Cohen, with whom he worked until her death in 2002. He shared shows with Olmsted, Cohen, Robert Squeri, Roland Wise, Frank Altamura, and Martha Vissert’hooft. He and Cohen opened the Zuni Gallery on Potomac Avenue in 1963—the first gallery to show Pop and Op Art, even before the Albright.

Perrone describes himself as a “peripheral war protestor” in the 1960s and 1970s, as he first immersed himself in this community of artists. He produced antiwar posters and managed an experimental theater of the sort whose principal subjects are social and political. He says his painting—which comprises splattering paint on canvasses and then drawing into the paint—has always been “on the dark side.” He greatly admired the work of Francis Bacon.

“I think he was the best artist of that century. He was a very dark artist who confronted the realities of the day. When I look back on it, the important work that artists do always has to do with the social scene. I never would have said that at that time. Ensor, Goya…those are the great artists in my mind. Those are my heroes.”

In the early 1970s, Perrone took a break from painting and did not return to it in earnest until about 20 years ago, when he remodeled a warehouse as a studio and living space. It was then that he took up war as his subject, too, producing a series of drawings of survivors of the conflict in Kosovo. (Those drawings will be exhibited at Buffalo Big Print on Allen Street later this month.) A few years ago, he turned his attention to sculpture and began experimenting with the use of paper bags as a modular building material for his work. His first effort failed but led to a brainstorm: He would use small bags to build a sculpture depicting the prow of a ship emerging from a wall. The bags—4,000 of them in all—would contain the names of soldiers who had died in Iraq, symbolizing wasted, unfulfilled lives, and creating a sort of digitalized image of the ship of state to which they had been sacrificed. The piece is called Illusion/Delusion, and was recently acquired by the Burchfield-Penney. It will go on exhibit immediately after War Ongoing Project comes down, in two months.

Perrone conceived War Ongoing Project along similar lines as Illusion/Delusion: as an opportunity to remind people that the consequence of war is death and destruction, and death and destruction damage societies, retard their progress.

“The bags serve as a reminder to people to think about these casualties,” he says. “We don’t see body bags today. People aren’t as concerned as they should be, as they were during the Vietnam War, when there were a lot of protests, a lot of images of war—fighting, dying.”

There are 10,000 names contained in the bags that War Ongoing Project comprises, less than one-sixth of the American lives lost in Vietnam. (To say nothing of the Vietnamese lives lost, both military and civilian.) Those lives are lost not only to the men who died and their loved ones but to society. Add those losses in potential to the wealth that wasted in war—to enrich the companies that build the war machine, in destroying property—and then consider how that wasted wealth might have alleviated the current healthcare crisis, for example.

“When you consider all the money we’ve lost in these wars, which have been pretty arbitrary—where not enough has been done to negotiate rather than jump into a war—we could have a much better society. We could have better education systems, we could have more people at work. We could really do things.”

After Burchfield-Penney director Ted Pietrzak purchased Illusion/Delusion, Perrone proposed the installation as well. When the proposal was accepted, he spent three months prefabricating elements of the installation in his studio. In that time, he also sought out collaborators, both for his installation and to create a program of artworks of in various media and venues, all feeding a conversation about the price of America’s endless wars. The Burchfield-Penney will host two panel discussions this month, one composed of veterans who write about their experiences (Saturday, April 10, 2pm) and the other composed of veterans who make visual art about their experiences (Sunday, April 25, 2pm).

The gallery will also host two theater pieces—one produced by Scott Behrend of Road Less Traveled Theater and the other by Vincent O’Neill of the Irish Classical Theater. Joseph Krysiak, for whom Perrone once designed a set in the 1960s, will do a reading as well.

Rocco La Penna, who helped gather some of the interviews used in the installations audio component, will perform a piece called Pvt. Wars starting April 8 at Rust Belt Books. (Other contributors to Perrone’s installation include Greg Condon, Tim Leary, Bob Stubley, and Andrew Hutner.)

There will be a series of war-related films screened at both the Unitarian Universalist Church at Elmwood and West Ferry and at St. Luke’s on Richmond Avenue. The film series is curated by the Burchfield-Penney’s Don Metz.

Billy X Curmano, a Vietnam veteran who once swam the length of the Mississippi River, will perform a piece called Midnight Babylon by Reggie McCleod, which premiered at the Cat Club in New York City. That takes place Friday, April 23 7pm, at the Burchfield-Penney.

Composer KG Price will perform a piece called Terra/Cysts for prepared toy piano, voice and Max/MSP at the Burchfield-Penney. And ArtSpace on Main Street will host an exhibit of war-related paintings by Buffalo artist Geoff Krawczyk. That shows opens April 10 with a reception at 7pm.

Ben Perrone’s installation will be exhibited through May 30. There will be an opening reception on Friday, April 9, 5:30-8:30pm. For more information about the exhibit and its attendant events, visit www.burchfieldpenney.org.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n14 (Week of Thursday, April 8th) > Lives Lost This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue