By Frank Parlato

Cancer treatment lives on hope. Doctors rarely promise a cure; they promise “management.” “Time.” “Stability.”

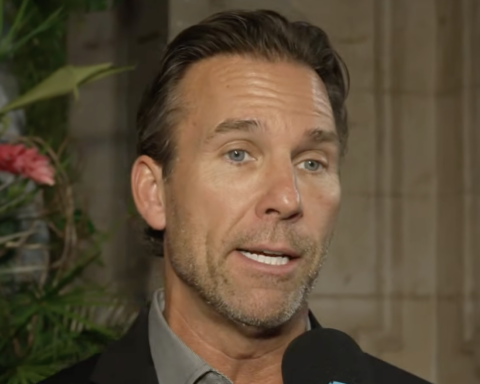

Dr. Jason Williams runs his clinic in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. His patients cross a border out of desperation because U.S. medicine has no cure for them.

Dr. Williams does what U.S. regulators forbid. He came to Mexico quietly. In a treatment room at H+ Hospital, Williams, freed from US regulations, practices the way he thinks cancer can be killed.

30 YEARS OF MARGINAL PROGRESS

Over the last three decades, cancer treatment has improved somewhat. Childhood leukemias, Hodgkin lymphoma, and testicular cancer have high cure rates. But for many solid tumors — pancreas, liver, brain, and advanced metastatic disease — progress has been marginal.

Step One — Damage the Tumor So the Body Sees It

Cancer begins when a cell’s DNA breaks and the cell behaves like an invader — multiplying without purpose, infiltrating tissue, spreading without regard for the life of its host. Williams’s method is to try to force the immune system to recognize the invader and attack it.

He uses image-guided ablation and pulsed electric fields to wound the tumor. When the cells break apart, they release their antigens — the molecular signatures of the cancer. Those signals give the immune system a clearer target, a reason to recognize the tumor as something it must confront.

Step Two — The Cocktail

Williams uses drugs like Opdivo, Keytruda, Yervoy, LAG-3 inhibitors, and others in combination. Cancer survives by exploiting several escape routes at once: it can blunt the T-cell response, conceal its antigens, or redirect its growth signals when one pathway is shut down.

Each drug he uses targets a different escape pathway. The goal is to block all of them so the tumor can’t adapt.

He studies each patient’s scans, their genetic mutations, and the patterns in their immune markers. In the treatment room, the work becomes more exact: with ultrasound, he guides a needle into the tumor itself and delivers the drugs directly into the microenvironment where the disease lives.

Patients return often as he adjusts the drug combinations based on how the tumor responds.

In the United States, doctors cannot mix untested drug combinations, inject them into tumors, or change doses week to week unless they are running an FDA-approved trial.

Major cancer centers are studying the same idea — putting drugs straight into the tumor. Early trials show that delivering immune therapies this way may make them work better.

The FDA Stops the Work

The rules exist because unsafe drug combinations have caused harm. Regulators want proof before they allow anything new. But this is hard on people who are dying and cannot wait years for a trial to end.

This Was Legal in America

Before 1962, the FDA focused mainly on basic drug safety. Doctors did not have to prove a drug worked, and formal trials and combination testing were limited.

After 1962, this kind of bedside experimentation needed FDA approval through an Investigational New Drug process, which made it almost impossible in everyday practice. In the 1950s, a doctor using aggressive drug combinations on patients with no other options was often seen as an innovator.

So Williams works in Mexico, one of the few regions where the law still permits this degree of physician-guided experimentation, provided informed consent is given.

The FDA has no authority outside the United States. It cannot regulate a foreign clinic, ban a procedure done abroad, or punish a U.S. doctor for using unapproved drug combinations outside U.S. borders.

Dr. Williams is legal.

This is why American physicians run innovative clinics overseas — offering stem-cell therapies, gene therapies, CAR-T variants, virotherapy, and intratumoral and immunotherapy in countries where such work is permitted.

The Results & The Uncertainty

In his published prostate cancer trial, Williams reported a 53% complete response rate — ten times higher than standard U.S. treatment. The results haven’t been independently replicated yet, but for patients with no other options, hope is more than U.S. oncology offers.

If he treats a patient earlier — before the cancer has spread, before it has mutated its way past standard treatment — his results are better.

Most patients come to Williams after chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery have failed. Chemotherapy kills immune cells along with tumor cells. Radiation scars tissue and makes tumors harder to reach. Surgery removes what can be seen, but microscopic cells often remain and grow back stronger.

Did Regulation Help or Hinder?

In the U.S., the outlook is grim. For pancreatic, liver, brain, ovarian, metastatic colorectal, and most metastatic cancers, cure rates have stayed low for more than sixty years. Science moved forward, but cures did not.

Scientists decoded the cancer genome, mapped immune pathways, and developed targeted drugs, advanced imaging, and treatment technologies.

But the clinical system have not use these discoveries quickly enough, and breakthroughs in the lab rarely translated into cures in the clinic.

If today’s FDA rules had existed in the 1950s, the rapid development of childhood leukemia cures would likely have been delayed — possibly by decades.

If doctors had been free to do that since 1960, we might have discovered curative combinations in the 70s or 80s, the same way AIDS treatment transformed the moment combination therapy was allowed.

Cancer kills ten times more Americans than AIDS ever did, but no president ever declared a cancer emergency. When AIDS activists demanded faster drug approval in the 1980s, politicians responded because inaction became politically fatal. Cancer deaths — slow, private, statistically dispersed — never generated that pressure.

But there’s another reason cancer never got the same urgency: the economics are different.

The oncology industry generates over $200 billion annually in the United States alone. Pharmaceutical companies profit more from drugs that extend survival by months than from treatments that eliminate disease entirely. Keytruda generates $25 billion a year because patients stay on it indefinitely.

A patient “managed” for two years before dying generates roughly $600,000 in revenue across drugs, procedures, imaging, and doctor visits. A patient cured in three months? Maybe $60,000. The entire system is structured around long-term management, not rapid elimination of disease.

From a 2018 Goldman Sachs biotech research report titled “The Genome Revolution”:

“Is curing patients a sustainable business model?”

“One-shot cures offer tremendous value for patients and society, but they challenge developers seeking sustained revenue.”

Translation: cures erase customers.

When Gilead cured Hepatitis C in 12 weeks, the Hepatitis C treatment market collapsed. Their revenue fell 90% because they had eliminated their own customer base. Wall Street punished the stock.

Williams’s approach threatens to do the same to a $200 billion oncology industry.

The FDA’s regulatory structure — requiring years-long trials of single drugs before allowing untested combinations — doesn’t just protect patient safety. It protects an economic model that depends on incremental progress and long-term management rather than rapid cures.

In a clinic by the sea…

Williams performs the kind of immunotherapy the FDA won’t permit — injecting combinations of drugs directly into tumors, using pulsed electric fields to rupture cancer cells, exposing tumor antigens so the immune system finally sees what it missed.

For patients with no remaining options, Jason Williams offers a path the U.S. system does not allow.

A dying patient may refuse treatment and slip away on his own terms, yet he is barred from pursuing an unapproved therapy that might prolong his life. The protection comes at the wrong moment, for the wrong purpose, and the people it affects have no time left.

Call him what he is: Jason Williams is a hero to the patients the system has already written off.

To contact Dr. Williams, visit williamscancerinstitute.com

His book, The Immunotherapy Revolution: The Best New Hope For Saving Cancer Patients’ Lives, is available on Amazon, and he offers a full, free audio version on his website.