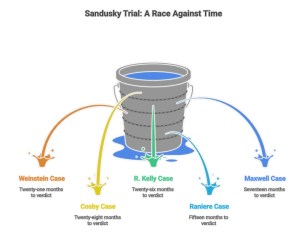

Seven months from indictment to conviction. Forty-eight counts. Ten alleged victims.

It did not need to be fair.

Jerry Sandusky was indicted on November 4, 2011. He was convicted on June 22, 2012. Seven months and 18 days.

Compare the time to other high-profile sex abuse cases:

Harvey Weinstein

Indicted May 2018. Convicted February 2020.

Five counts. Three victims.

Indictment to verdict: twenty-one months.

Bill Cosby

Charged December 2015.

Convicted April 2018.

Three counts. One victim. One incident.

Charges to verdict: twenty-eight months.

R. Kelly

Indicted July 2019. Convicted September 2021.

Nine counts. Six victims.

Indictment to verdict: twenty-six months.

Keith Raniere

Arrested March 2018. Convicted June 2019.

Seven counts. Multiple victims.

Arrest to verdict: fifteen months.

Ghislaine Maxwell

Indicted July 2020. Convicted December 2021.

Six counts. Four victims at trial.

Indictment to verdict: seventeen months.

Seven months made it impossible for Sandusky to have an adequate defense.

Victim Background Investigation

In multi-victim sexual abuse cases, standard practice allows two to three months of investigation per accuser.

With ten adult accusers who testified that they were abused when they were teens, that means 20-30 months of work.

Sandusky’s defense had six months.

That mattered because the case rested on testimony.

There was no DNA. No physical evidence. No medical records. Not a single outcry at the time when these adult witnesses were teens.

The case turned on credibility.

Expert Witness Development

The prosecution had the full resources of the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office. Its experts were ready.

The defense had to find its own.

The issues were:

False memory.

Suggestive interviewing.

Delayed disclosure.

Recovered memory.

Several of these adult accusers had no memory of abuse until investigators or civil lawyers approached them. Only then did memories appear.

Repressed recovered memory “science” must be explained to a jury. Without experts, it cannot be.

The defense never had the chance.

Institutional Records

The prosecution’s story ran through Penn State’s facilities, The Second Mile charity, and decades of records. Emails. Personnel files. Facility access logs. Second Mile and Penn State documents spanning from 1977 to 2011. Reviewing material like that takes eight to 12 months when done properly.

There was no time.

Discovery Dumps

It got worse.

Critical discovery arrived ten days before trial, withheld by the prosecutors until the last minute. You cannot investigate what you have not seen. You cannot cross-examine what you received days before the trial.

The Pressure Cooker

After the indictment in November 2011, the ground shifted fast. Five days later, Penn State’s trustees fired Joe Paterno, the winningest coach in college football. Students rioted. The campus broke apart.

Two months later, Paterno died.

By early 2012, the NCAA was threatening the death penalty. State College faced ruin. The town lived on the school. The school lived on football. The university needed closure. The NCAA wanted a resolution.

The Attorney General’s office, which had waited three years to indict, now needed speed.

The pressure for a quick conviction was immense.

In any other case, in any other town, without a ruined football program and a dead legend, the defense would have been given time. In any other case, the fast schedule alone would have demanded appellate review.

The rules that protect every other defendant did not apply to Jerry Sandusky.

The Meeting That Sealed It

Everything has an origin. For Sandusky, it was not the indictment. It was not the media frenzy. It was a hotel.

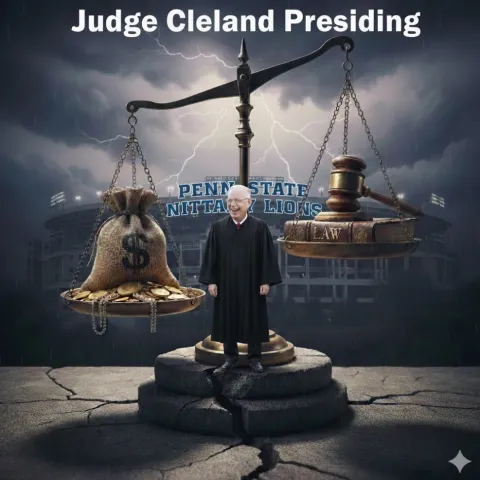

On December 12, 2011—five weeks after his arrest—a meeting took place at the Hilton Garden Inn in State College, Pennsylvania. Present were Judge John Cleland, senior prosecutor Frank Fina, lead prosecutor Joe McGettigan, and Sandusky defense attorney Joseph Amendola.

There was no court reporter. No recording. No transcript. No docket entry. No public notice.

The defendant was not there. He did not know the meeting was happening.

Defense co-counsel Karl Rominger—the lawyer most likely to object—was not told. He learned of the meeting years later. What came out of that small hotel conference room was the path to conviction. At the meeting, it was agreed to waive the preliminary hearing scheduled for the following day.

Sandusky’s constitutional right to challenge the evidence was surrendered. A trial schedule was imposed: seven months for one of the most complex criminal cases in Pennsylvania history.

No one can tell you what was said. There is no record. That was the point.

You do not meet in a hotel, leave the court reporter behind, exclude the defendant, and cut out the defense lawyer who would object unless you do not want a record of what you are agreeing to.

The Discovery Dump

What followed was no coincidence. Ten days before trial, prosecutors dumped twelve thousand pages of discovery on the defense. Twelve thousand pages. Ten days.

Defense counsel Amendola asked for a continuance. Cleland denied it.

Amendola asked to withdraw. He told the court he could not competently represent his client. The Rules of Professional Conduct require a lawyer who cannot provide competent representation to step aside.

Cleland denied that.

A judge cannot force an unprepared lawyer to try a case any more than he can force a lawyer to betray privilege. Amendola should have refused and taken contempt. He did not.

The trial began. Eleven days later, the verdict came in.

The Sixth Amendment Question

Perhaps Cleland believed Sandusky was guilty. Perhaps he believed delay would only prolong damage to the football program.

That is human, though not judicial.

Judges should not decide guilt in advance. In fact, they should not decide guilt at all – that is up to the jury.

When a judge, prosecutors, and defense counsel meet in secret to waive rights and impose a schedule that the defendant cannot survive, the Sixth Amendment is forfeited.

The Recusal

Four years later, Sandusky’s post-conviction counsel discovered the hotel meeting. They raised it in PCRA proceedings. They included a footnote renewing the request that Cleland recuse.

Being caught, Judge Cleland admitted to the meeting. But he did not calmly explain it. He did not justify the absence of a record. He did not explain why the defendant was excluded.

Instead, he ordered counsel to remove the footnote. Delete it. Make it disappear.

They refused.

Cleland did not go quietly. When post-conviction counsel first moved to recuse him, he denied the motion. Only later, after counsel refused to withdraw the footnote, did he step aside.

Cleland did not declare a mistrial, which would have provided Sandusky with a new trial.

He recused, and after stepping aside, Cleland wrote a letter to the replacement judge, contesting Sandusky’s references to the hotel meeting. A recused judge reaching back into a case he had just left to argue with the lawyers who had exposed him.

A judge confident in his conduct answers questions. He puts reasoning on the record. He does not order arguments erased.

There was no reasoning that could survive daylight. He tried to bury the issue. When that failed, he left—loudly, angrily, with his thumb still on the scale.

The judge who held a secret meeting with no record, no defendant present, and no co-counsel informed also recommended disciplinary action against the lawyers who discovered it.

The Bottom Line

The preliminary hearing was forfeited. The rushed trial had produced a conviction. Penn State had paid more than $60 million in settlements to the adult victims who testified to abuse when they were kids.

No legitimate reason that no record was kept. No legitimate reason the defendant was excluded. No legitimate reason for cutting out the defense lawyer, who was likely to dissent.

There is no legitimate reason a judge, who had done nothing wrong, would try to suppress the issue, recuse in anger, and continue interfering after stepping aside.

In any other case, a secret, unrecorded meeting between a judge, prosecutors, and one of two lawyers of the defense counsel—where constitutional rights were waived and an impossible trial schedule imposed—would require reversal.

In any other case, the judge’s behavior after exposure would confirm the impropriety.

But this was Jerry Sandusky.

And the hotel meeting is where the fix went in.