The Frank Report received tips about Rachel Grynberg.

More than one. The callers spoke with certainty. They called her “Hurricane Rachel.” They said she had inherited a billion-dollar oil empire and used it to wreck companies and careers in courtrooms across the country.

We looked into it.

What we found was not what we were told. It was more complicated. In some ways, it was more troubling.

The tipster sent documents in batches. Dozens of them. We read them all. We went through every case, every deposition transcript, every court filing.

They told a long story of litigation. But it was not Rachel’s story. It was her father’s.

The filings belonged to Jack Grynberg. His lawsuits. His battles. His history.

We were not given a single case filed by Rachel Grynberg against any third party after she took control of the family companies.

Not one.

The “Hurricane Rachel” story did not check out. At least not yet.

But the story behind the story — how Rachel Grynberg came to control a billion-dollar empire and what happened to the women who said her father was a sexual predator — is worth telling. Because nobody else has told it.

The Empire

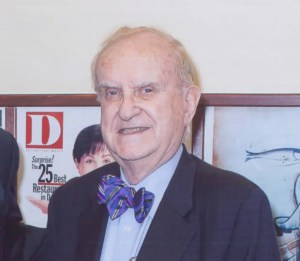

The Grynberg fortune begins with Jack.

Jack Jakob Grynberg was born in 1932 in Brest, Poland. He was seven years old when the Nazis invaded. His family fled to Ukraine, returned to the Brest Ghetto, escaped before it was liquidated in 1942, hid in a barn for nearly two years, and spent the final months of the war in the forests with partisans. After the war, he lived in a displaced persons camp, made his way to Palestine, fought in the Israeli War of Independence with the Irgun, and eventually arrived in Denver, Colorado in 1949 with twenty-seven dollars in his pocket.

He got the only international scholarship at the Colorado School of Mines. Graduated in two and a half years. Earned a master’s in petroleum engineering. Made his first million by thirty by reworking a gas well that Amerada Hess had abandoned as noncommercial. He was right and they were wrong, and that set the pattern for the next sixty years.

Jack Grynberg’s great discovery was the Kashagan Field in Kazakhstan — one of the largest oil finds in the world in the last half century, estimated to hold nine billion barrels of recoverable oil and twenty-five trillion cubic feet of natural gas. He got there by cultivating a relationship with Nursultan Nazarbayev, the president of Kazakhstan, who let him call him by his first name — a signal of closeness in that culture that opened doors no American oilman had ever walked through.

The major oil companies — BP, Shell, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips — came in behind Grynberg, and then, as majors tend to do, tried to cut him out. Jack sued them all. He filed more than seventy lawsuits accusing hundreds of firms of defrauding the government of mineral royalties. He fought BP, accused Exxon and Conoco of participating in bribery schemes, and tangled with foreign governments from Grenada to Cameroon to Ecuador.

A federal judge wrote that Grynberg’s “litigation exploits verge on the legendary.” A law professor used the Grynberg family as a case study in the UC Irvine Law Review alongside Sumner Redstone — two aging tycoons who held on too long and watched their families fight for what they built. The professor called it the “King Lear Problem.” Shakespeare would have recognized Jack Grynberg immediately.

Jack Grynberg was not a man who avoided courtrooms. He lived in them.

In the 1990s, he placed his companies — Pricaspian Development Corporation, Gadeco, and RSM Production Corporation — in the names of his wife Celeste and their three children: Rachel, Stephen, and Miriam. The purpose, as a judge later found, was to protect his wealth from creditors, estate taxes, and kidnapping threats. The understanding, Jack claimed, was that he would run the companies until the day he died.

At their peak, these entities held hundreds of millions in cash reserves, pulled approximately $120 million per year in royalty payments from Kazakhstan alone, and controlled exploration projects spanning multiple continents. The family pocketed roughly $160 million over twenty-three years while Jack did the work.

Then they fired him.

The Takeover

By 2014, Jack Grynberg’s behavior was changing. He was in his eighties. His children would later testify that he had become erratic — claiming to own a Wyoming oil well containing thirty billion barrels (more than the entire nation’s reserves), telling the president of Botswana he had two billion dollars in a local bank, trying to buy one hundred million dollars in generators for a Nigerian power plant that did not exist. A geriatric psychiatrist would later testify that Jack had dementia by 2014 and was sending bank information to a Gmail address he believed belonged to a Brazilian princess who had been dead for a decade.

In September 2015, the Pricaspian board voted to remove Jack as an authorized signatory on the company’s bank accounts. In February 2016, the board removed him as president and appointed Rachel and Stephen as co-interim CEOs. In March 2016, they removed him from the board entirely.

Jack fought back. He filed suit in Texas, claiming his children were violating a lifetime agreement. The case was moved to Colorado. A jury found there was no oral contract granting him lifetime control. A judge ruled he was not entitled to a penny in back pay for the decades he spent building the empire his children now owned.

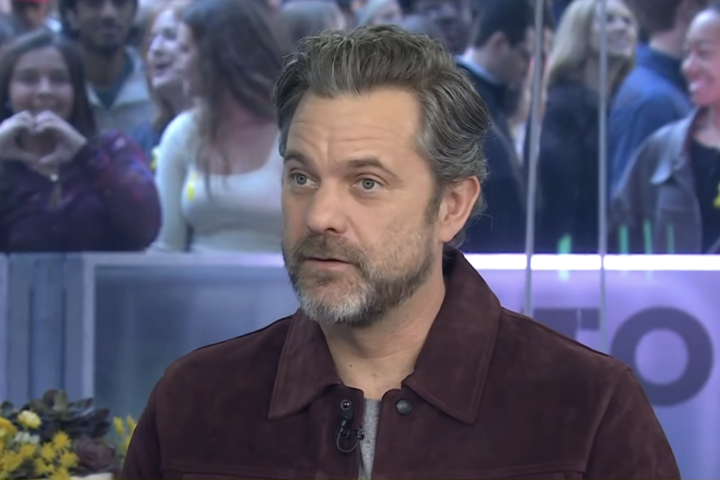

Rachel led the fight. She is now CEO of RSM Production Corporation and the registered agent for Gadeco Royalties LLC. She and her siblings control the entire apparatus — the Kazakhstan royalties, the domestic exploration rights, the cash reserves, and the litigation portfolio that Jack spent a lifetime assembling.

Jack Grynberg was placed in a care facility. He died on October 11, 2021, at the age of eighty-nine.

His attorney said Jack’s children, without having made any contributions to the companies, had received approximately one billion dollars that he alone had earned. The family’s lawyer said they were “relieved to have this unfortunate and painful litigation behind them” and that they had acted “to protect the companies and Jack Grynberg’s legacy.”

Whether the children were right to take the companies from a man with dementia is a fair question. The courts said yes. Reasonable people can disagree about whether the courts got it right or whether the children could have found a way to protect both the companies and their father’s dignity. But Jack Grynberg put those companies in his children’s names. He created the legal structure they used to remove him. That is not in dispute.

What is in dispute — or rather, what has never been discussed at all — is what happened to the women.

The Women

In April 2015 — one year before Rachel and her siblings formally ousted their father — Candice Dee Smith was working as Jack Grynberg’s personal assistant.

Smith claimed in a Douglas County lawsuit that Jack had bought her a $600,000 home in Parker, Colorado, furnished it, and let her live there for free with her then-husband and five children. Then the bill came due. According to the lawsuit, Grynberg ushered her into his office bathroom one day and told her it was “time for you to start repaying me” for the house.

The lawsuit alleged she was coerced into sexual contact thirty-five times over several months.

The Frank Report will note what the reader is already thinking. Thirty-five times is not one moment of coercion. It is not a single act of force from which a victim could not escape. It is an ongoing arrangement over a period of months. Smith alleged coercion, and coercion is real — a $600,000 house and a job create pressure that should not be minimized. But the allegation also raises questions about the line between coercion and complicity that Smith herself would have had to answer if the case went to trial. The Frank Report does not know whether it did.

Smith was not the only woman to make allegations.

Maxine Yzaguirre worked as a receptionist at Grynberg Petroleum for five months in 2016. She claimed Jack gave her tasks requiring her to bend over while he stared, that she walked into his office and found him in his underwear on at least three occasions, that he thrust himself at her and asked if she was interested, and that after she rejected a kiss he reminded her he had just given her a bonus.

Roxanne Alvarez, Maxine’s sister, worked as a temporary assistant. She alleged Grynberg took her to his home to do tasks while staring down her shirt. On a separate occasion, she claimed he lured her into the men’s locker room at the company’s Denver offices, kissed her, and put his hands inside her bra. She pulled away and ran. Alvarez reported the locker room incident to police. Grynberg was arrested in December 2016 and charged with felony unlawful sexual contact. The Denver DA later dropped the charge, saying it could not be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

Alvarez also reported the assault to Terence Burns, the company’s vice president. According to the lawsuit, Burns told her to stay quiet and not put their jobs at risk. He said Grynberg had done this before.

Burns and company attorney Roger Jatco were named as defendants for allegedly knowing about Jack’s conduct and failing to protect employees.

A fourth woman, Suzanne Greene, did not join as a plaintiff but submitted a sealed affidavit. She said she was harassed in 1976, just weeks after being hired as Jack’s executive secretary. She said he asked her to show a visiting associate “a good time,” then later came to her home, pinned her to a wall, and forcibly kissed her. When she pushed him off, he said, “But you invited me over.” Greene resigned in 1977 and said she did not go to authorities because she did not think they would believe her.

The allegations span forty years. The pattern described by Burns — “he has done things like this before” — suggests it was well known inside the company.

The Question

Here is what we know about the timeline.

Rachel Grynberg and her siblings began their legal campaign to remove their father in 2015-2016. Their theory was that Jack was mentally declining, making irrational decisions, and putting the family’s billion-dollar empire at risk.

During that exact same period — 2015 and 2016 — four women were alleging that Jack Grynberg was using the same company as a vehicle for sexual predation. One woman said she was coerced into sex dozens of times. Another was allegedly assaulted in a locker room. A company executive acknowledged the pattern and told a victim to keep quiet.

The family’s lawsuit to seize the companies and the women’s lawsuit were proceeding simultaneously, in the same metropolitan area, covered by the same newspaper.

What did Rachel do for those women? What did any of the Grynberg children do?

We do not know.

It is possible that the Grynberg family quietly settled the women’s claims, ensured they were compensated, and required confidentiality as a condition. If so, that would be a responsible resolution — and by its nature, we would never know about it.

It is also possible that the family took the money, took the companies, and left those women to fight one of Denver’s wealthiest families alone.

The Frank Report does not know which of these is true. No one in the Grynberg family has ever said a word about those women publicly. Not Rachel. Not Stephen. Not Miriam. In the age of #MeToo, a billion-dollar family that built its entire legal strategy around the argument that their patriarch was unfit has never acknowledged the women who may have had the most to say about just how unfit he was.

Maybe the silence means the matter was handled privately and responsibly. Maybe it means something else.

What We Are Looking For

The Frank Report received tips alleging that Rachel Grynberg has engaged in a pattern of aggressive litigation and destruction of business relationships since taking control of the Grynberg empire. We reviewed the materials those tipsters provided. Most of it documented Jack Grynberg’s legendary litigation history — not Rachel’s. What we were not given was a single case filed by Rachel Grynberg against any third party since she took control. Not one.

That does not mean such cases do not exist. The Grynberg family operates behind a wall of sealed records and corporate privacy. But tips dressed up as Jack’s old court filings do not get the job done. If people have been harmed by Rachel Grynberg’s stewardship of these companies, the evidence needs to be specific — case numbers, jurisdictions, names.

We are specifically seeking information on two fronts.

First, the disposition of the sexual harassment and assault lawsuit filed by Smith, Yzaguirre, and Alvarez in Douglas County. Was it settled? On what terms? Did the Grynberg family companies participate? Were non-disclosure agreements signed?

Second, the current status of Terence Burns and Roger Jatco. Once the Grynberg children took control, Burns and Jatco became their employees. Burns was accused under oath of telling a victim to stay quiet. Jatco was accused of knowing about the pattern and doing nothing. Did Rachel fire them? Did she keep them? The answer tells you something about what kind of company she chose to run.

Jack Grynberg built his fortune by fighting companies that were bigger than he was. His daughter inherited that fortune by fighting the man who built it. Whether the women her father allegedly victimized were taken care of or thrown away is a question the family has never answered.

We invite Rachel Grynberg to contact The Frank Report at any time with her perspective. If she took care of those women, she should say so. If confidentiality agreements prevent her from discussing the terms, a simple acknowledgment that those women existed and that their experience mattered would cost nothing.