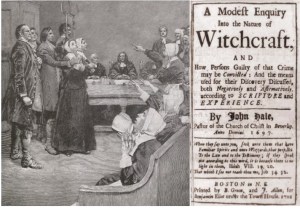

In 1692, the colony of Massachusetts killed twenty people for witchcraft. The evidence was overwhelming. Confessions, eyewitness testimony, and young accusers whose bodies convulsed theatrically in the presence of the accused.

The community was certain. Everyone believed. The courts were certain. Everyone knew someone who knew someone who swore they had seen the Devil’s hand at work.

To question the proceedings was to risk being accused yourself. And so thinking became dangerous.

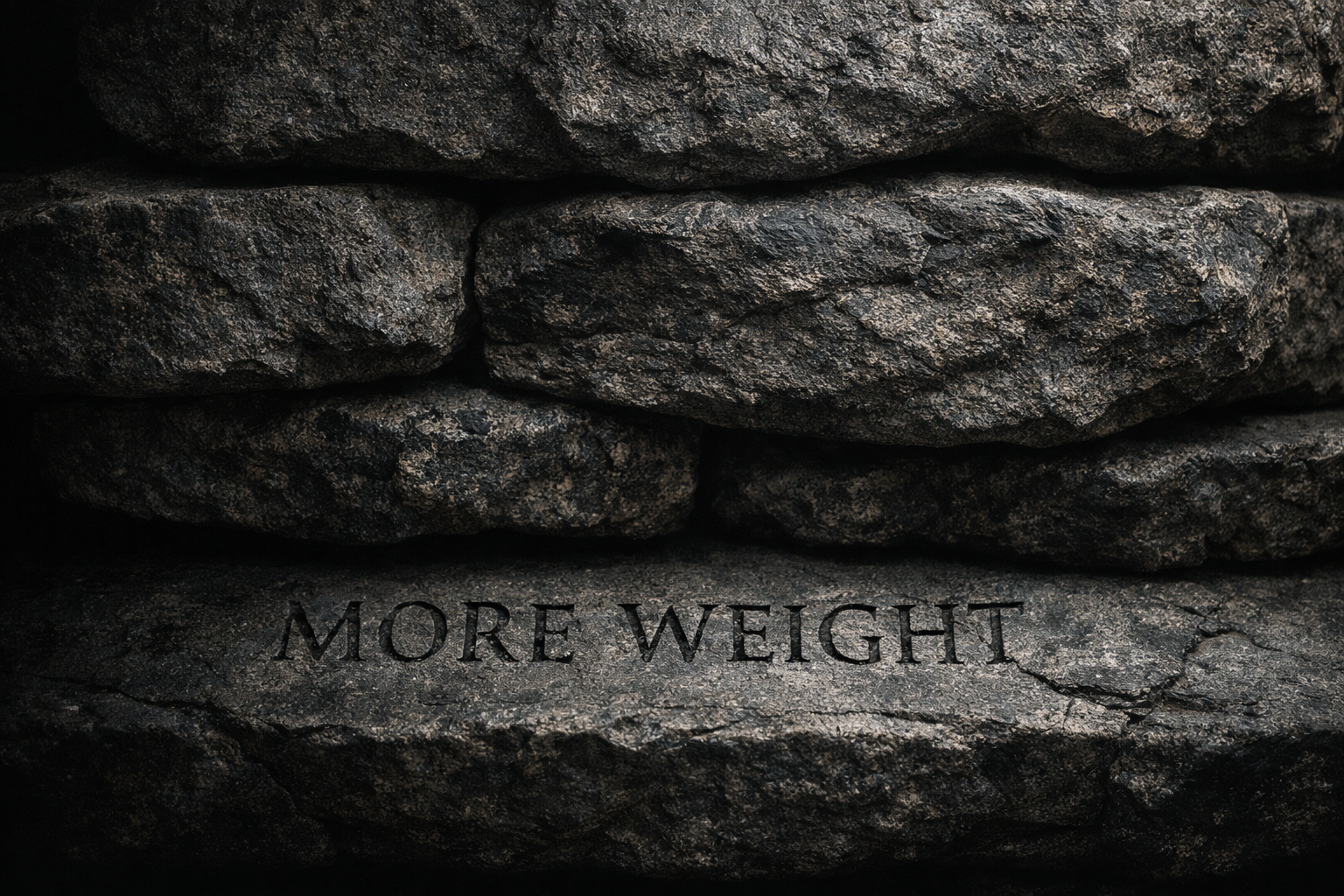

They hanged nineteen from the gallows. They stripped old Giles Corey naked, laid him on the ground, and crushed him slowly to death over two days beneath heavy stones. He said only, “more weight.”

Corey refused to enter a plea. Under the law, they couldn’t try him without a plea, so they used peine forte et dure — pressing — to force one out of him.

If he had pleaded and been convicted, his property would have been forfeited to the colony. His family would have lost everything. By refusing to plead — by dying under the stones without ever saying guilty or innocent — he preserved his estate for his heirs.

“More weight” was a man choosing slow, agonizing death rather than confess to something he didn’t do.

They buried Corey and the other witches in shallow graves. Families were forbidden to mourn.

It took three hundred years for Massachusetts to admit it was wrong.

Not because the truth was hidden, but because people did not want to admit what they had done.

The judges who presided in Salem believed, as their community believed, that evil had descended upon them. The judges did not imagine themselves as villains.

When doubts came, they pushed them aside. When the accused included people of prominence and good reputation, when the “spectral evidence” seemed unreliable, when evidence grew thin, and confessions felt forced, none of it mattered.

The trials went on.

To say they were wrong would admit people had died because of them. So the executions continued until public opinion shifted so dramatically that the courts had no choice but to stop.

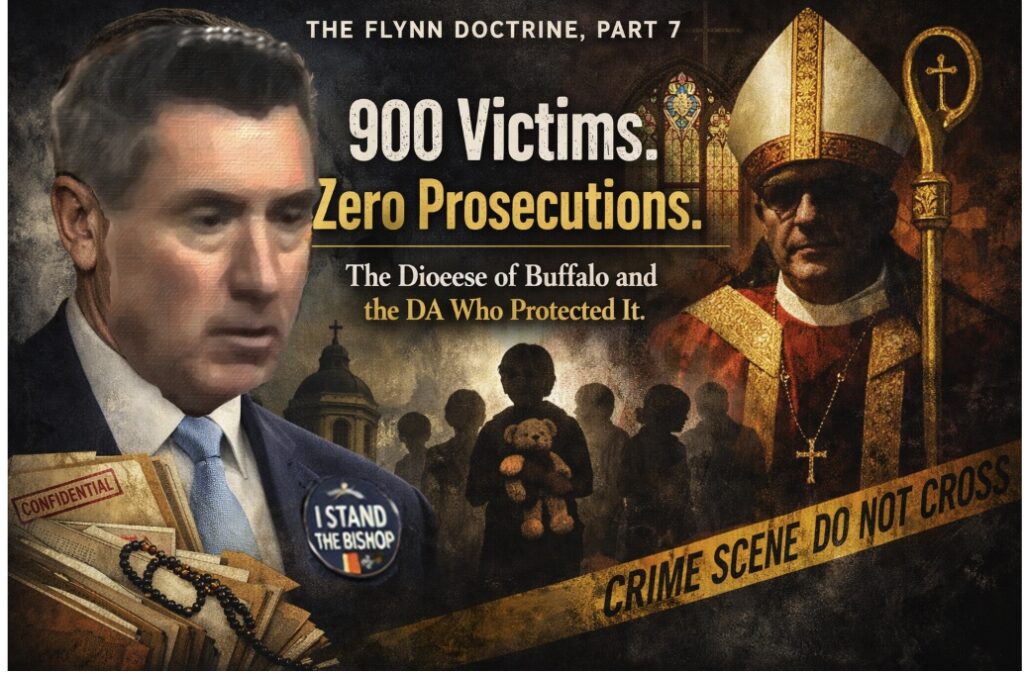

Every jurisdiction has its landmark, its defining prosecution. The one that made headlines, the case that assured the public the system was vigilant and strong. In Pennsylvania, that case is Jerry Sandusky.

People say that name in Pennsylvania, and everyone knows what it means. The 2012 conviction was not merely a verdict. Penn State paid more than $100 million in settlements. The NCAA levied historic sanctions. A bronze statue was removed in the night.

Careers were destroyed, reputations annihilated, and an entire university system reorganized itself around the belief that a monster had operated in plain sight and the institution had failed to stop him.

Something terrible had gone unnoticed, and the narrative was fixed before the trial began.

The Slow Burn

Jerry Sandusky entered prison at 68. He is now eighty-one. He has spent 13 + years in Pennsylvania prisons. Five years in solitary confinement — twenty-three hours a day in a cell, minimal human contact, isolation that international human rights organizations classify as torture.

The witches of Salem at least had the mercy of a quick end.

Sandusky’s punishment is designed to stretch across decades — a slow incineration of a man’s years, witnessed by a public that believes he deserves worse.

Those Who Know

There is another kind of punishment, perhaps, reserved for those who know — the prosecutors who saw the evidence unraveling, judges who recognized the constitutional violations, journalists who understand the story has collapsed, Penn State administrators who paid settlements they knew were based on lies.

Then there are the accusers.

They cashed checks for millions of dollars in exchange for stories that grew more elaborate with each telling, stories that shifted to match what investigators needed to hear, that contradicted their prior statements and the physical record. Money changed hands. Stories changed, too.

They live in houses bought with that money, drive cars paid for with that money, raise families funded by the destruction of a man whose guilt they were taught—and taught themselves—to accept.

Every morning, they wake knowing. Every night they lie down with it. The money spends, but the knowledge compounds. It stays with a person long after the money is gone.

The witches were hanged on Gallows Hill. Maybe they found peace in eternity.

The question for those who participate in injustice — who know and do nothing, who profit and stay silent — is whether their judgment comes in this life or the next.

The question is whether judgment arrives now or later.

Why the Courts Resist

Now, thirteen years later, a post-conviction relief petition presents evidence that should trouble any honest observer. Witnesses whose accounts have collapsed under scrutiny. Financial incentives that preceded accusations. Prosecutorial conduct that, in any other case, would mandate reversal.

Twenty separate issues — any one of which, in a case without this cultural weight, would result in a new trial.

The Pennsylvania courts resist. The answer is human, not legal. If Sandusky is innocent — or even if his trial was fundamentally unfair — then every actor in the system faces a reckoning.

The prosecutors who built careers on the conviction were complicit in injustice. The judges who denied appeals failed their oaths. The university that paid $100 million in settlements did so for nothing — destroyed its legacy based on a lie. The media that canonized the narrative became instruments of a modern witch hunt. The public that demanded blood must confront its appetite for vengeance over truth.

And so the courts apply standards of review with unusual rigor. Procedural barriers materialize. The benefit of every doubt flows toward finality. Twenty issues become footnotes.

The Record We Are Building

This series will examine the Sandusky case with the same scrutiny we would apply to any criminal prosecution. We will review the evidence presented at trial. We will examine what has emerged. We will analyze the post-conviction proceedings and the Commonwealth’s responses.

A single brave judge did not overturn the courts of 1692. They were overturned by history — by a record so complete, so undeniable, that future generations could no longer look away.

Salem took three hundred years.

Sandusky has never confessed. Thirteen years, and he has never said the words they want him to say. He could have “admitted responsibility” when he was resentenced on November 22, 2019.

Sandusky choked up and said, “I apologize that I’m unable to admit remorse for this because it’s something that I didn’t do.”

Corey died protecting his family from a system that would have taken everything if he gave in. Sandusky is dying the same way — slowly, under the weight of a system that will crush him until he confesses or expires.

Corey could have stopped the stones with one word. Sandusky might have shortened his sentence with a few sentences of remorse at resentencing. Both men, given the opportunity to lessen or end their suffering by saying what the system demanded, refused.

But a man doesn’t express remorse for something he didn’t do. Even facing the stones. Even facing death in prison.

More weight.